Gaza’s catastrophe will have long-lasting impacts on lives and livelihoods

The humanitarian crisis in the Gaza Strip has reached catastrophic levels since the brief ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas war ended March 18. Famine thresholds have been surpassed in many parts of the territory, according to the latest Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) analysis. Increasing numbers of hunger-related deaths among children under 5 are being reported, and nearly the entire population of 2.2 million people now faces high levels of acute food insecurity. About one-quarter of them are facing catastrophic conditions marked by extreme hunger and risk of starvation.

Failing food assistance

As the IPC analysis emphasizes, nearly the entire Gaza population is now fully dependent on food assistance and other humanitarian supplies for survival. The territory’s infrastructure has been nearly fully destroyed and its people displaced numerous times, depriving virtually all of their livelihoods.

At the same time, humanitarian aid has been woefully inadequate. Israeli authorities have repeatedly denied requests by relief organizations for humanitarian access; aid convoys that have crossed the border have faced significant obstacles and danger. From March through mid-May, Israel imposed a complete blockade on humanitarian food deliveries, causing a rapid rise in malnutrition. Though it eased the blockade on May 19, only a trickle of humanitarian assistance, mainly food, has entered the Gaza Strip since, as reported by IPC.

Bakeries remain closed and community kitchens are unable to meet the massive scale of needs, lacking not only food supplies but also water and power. Meanwhile, the new Israel-U.S.-backed Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF), designated by Israel as the principal aid conduit, has proven to be highly ineffective and disorganized, failing to reach most people in need in Gaza. GHF has primarily delivered meals from three of four distribution sites located in the militarized zones along the Khan Younis-Rafah border—where less than a quarter of the population is located. International donors have recently stepped in with food airdrops. However, airdrops made in 2024 were mostly ineffective; thus, this approach is unlikely to have much of an impact on the humanitarian crisis.

A ceasefire and free-flowing humanitarian assistance could stave off a human catastrophe

An immediate ceasefire and political solution to end the war are urgently needed, but at the moment these do not seem anywhere in sight. Short of that, a ceasefire and restoring a free flow of humanitarian assistance by independent and competent providers (such as the United Nations agencies with vast experience in Gaza) could still avert a major famine, one that might rival the worst famines in modern history. But this would require rapid, large-scale action starting now and continuing in the space of weeks—not longer.

Even if such a catastrophe is averted, the people of Gaza will suffer long-lasting consequences. The war and food crisis will exact a collective toll on the population’s physical and mental health for decades to come. Moreover, the near-complete destruction of the territory’s infrastructure, local production capacity, and economic livelihoods will likewise lead to extended suffering, even when peace and security can be sustainably guaranteed.

Long-lasting consequences of severe malnutrition and loss of livelihoods

Famines often inflict irreversible intergenerational damage to human health. Undernutrition among infants disrupts physical growth, weakens the immune system, and impairs cognitive development. Evidence, for instance from the 1984 famine in Ethiopia, shows that surviving children tend to feel the impacts for the remainder of their lives—including stunted growth, chronic diseases, and reduced educational and economic potential. Malnutrition exacts a high economic cost through reduced human capital and productivity and increased health care expenses. Even with a quick restoration of livelihoods, these effects can perpetuate a vicious cycle of poverty, poor health, and low economic growth.

Restoring livelihoods in Gaza will require a sustained long-term effort. Rebuilding agricultural capacity should be central to this project. While pre-war Gaza was a highly urbanized territory, agriculture and food production were a longstanding mainstay of its economy. Even though the sector’s economic importance declined during previous episodes of conflict and occupation, by 2023 about 44% of household food consumption still came from domestic producers, according to the Palestine Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS).

In 2023, agricultural land occupied about 40% of the territory of the Gaza Strip (150.5 km2 out of a total of 365 km2). About 53% of agricultural land was devoted to vegetable and fruit cultivation, including tree horticulture for olives and citrus fruits. Wheat was the main field crop, as well as Gaza’s staple food, mostly produced in North Gaza and Khan Yunis. Agricultural products constituted more than 50% of the territory’s total merchandise exports.

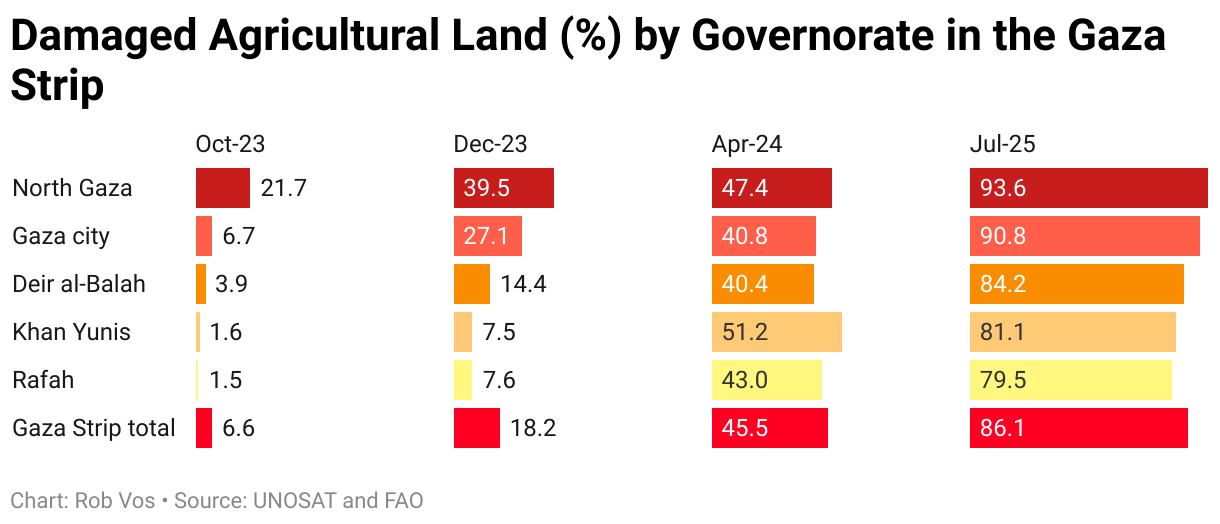

The current war has caused huge damage to agricultural land (Figure 1) and massive collateral damage to agricultural livelihoods and local food supplies.

Figure 1

Poor weather conditions and earlier conflicts had already degraded farmland, especially in North Gaza, where more than one-fifth was classified as damaged. From October 2023 on, the war caused more damage, and the intensification of Israeli bombardments and other hostilities since January 2025 has now led to the nearly complete destruction of agricultural land and production capacity.

The most recent analysis by the United Nations Satellite Centre and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), from July 2025, indicates that 86% of agricultural land is now considered to be damaged, up from 45.5% in April 2024. The situation is worse in North Gaza and Gaza City, with over 90% of agricultural lands now damaged.

This assessment is based on a comparison of the density and health of vegetation and crops over the past six agricultural seasons. It uses a method known as normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) analysis and a multi-temporal classification to identify notable changes taking place in agricultural areas during that time frame. Figure 2, also accessible with further information on IFPRI’s Food Security Portal, compares the situation in October 2023 with that of July 2025.

Figure 2

Along with the damage to agricultural land, much of Gaza’s infrastructure of greenhouses has also been destroyed. Consequently, much of the territory’s capacity to produce vegetables and fruits is now gone, as it is for other crops and livestock. As a result, domestically-produced food supplies have been virtually wiped out, and Gaza has lost 55% of its pre-war level of export earnings.

As a result, prices of commercially-marketed food supplies have skyrocketed, adding to the population’s now near-complete dependence on food assistance. Consequently, Israel’s August 5 announcement reopening borders for some commercial food imports into Gaza may provide little relief, as only very few in Gaza will be able to afford the cost of such food or even access it, given that market and distribution systems have collapsed, and travel is extremely dangerous.

Only a lasting peace arrangement can prevent future famine in Gaza

Gaza’s massive losses of life and human capital, along with the widespread damage to agricultural lands, trees, greenhouses, and other basic production infrastructure, will mean a long and arduous recovery. An essential first step is an immediate truce ending hostilities and allowing a large flow of food and other relief supplies to alleviate the unfolding catastrophe.

But this will only mitigate some small part of the war’s existing damage. Gaza needs a lasting political solution that will bring sustained peace and security, in order to facilitate the long-term investments necessary for recovery and reconstruction. Without that, history is bound to repeat itself in Gaza.

Rob Vos is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions (MTI) Unit; Soonho Kim is an MTI Senior Data Manager. Opinions are the authors’.