Outline

Multiple breadbasket failures in high-income nations impact global prices and incomes more than those in poorer nations. However, similar production shocks in developing countries cause significantly higher levels of poverty and food insecurity compared to shocks in wealthy countries.

Last update: December 2025

A new IFPRI Discussion Paper reviews the risks of multiple breadbasket failures (MBBFs) and their impacts on global food security. With 80% of the world’s population relying on maize, rice, and wheat, global food stability hinges on production concentrated in a few specific regions. Extreme weather events are increasingly affecting these multiple producing areas simultaneously. For instance, 2022 saw concurrent droughts in Europe and the United States, alongside devastating floods in Pakistan and heatwaves in India. Exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, these shocks significantly raised global food prices. The paper highlights that MBBFs heighten food insecurity through two distinct channels: reduced income for poor farmers suffering yield losses, and higher food prices for net buyers. Consequently, policymakers must determine whether to prioritize supporting consumers facing price spikes or producers losing their livelihoods—a decision that depends largely on whether the shock originates in wealthy or developing nations.

Key Findings

The comparative analysis of Multiple Breadbasket Failures reveals a stark divergence between financial disruption and humanitarian catastrophe depending on the location of the shock. A failure in the Global South creates a severe humanitarian crisis, characterized by a massive drop in national real income of over 5% for shocked Low- and Middle-Income Countries and a sharp rise in hunger, with the prevalence of undernourishment increasing by 2 percentage points globally and between 4 and 10 percentage points within the affected regions. Conversely, a failure in the Global North manifests primarily as a global market shock; while it drags down global average income due to the sheer economic size of the affected nations and drives up the cost of a healthy diet by over 14% in high-income regions, its impact on global food insecurity is paradoxically muted. This resilience in the face of a Northern shock occurs because producers in developing nations are able to expand production and benefit from higher output prices, which buffers them against the poverty and hunger that otherwise accompany rising food costs.

Source: Martin, Will; Nia, Reza; and Vos, Rob. 2025. Global food security impacts of extreme weather events and occurrence of breadbasket failures. IFPRI Discussion Paper 2360. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/176642

Click here for the full screen

Estimating global food security impacts of MBBFs

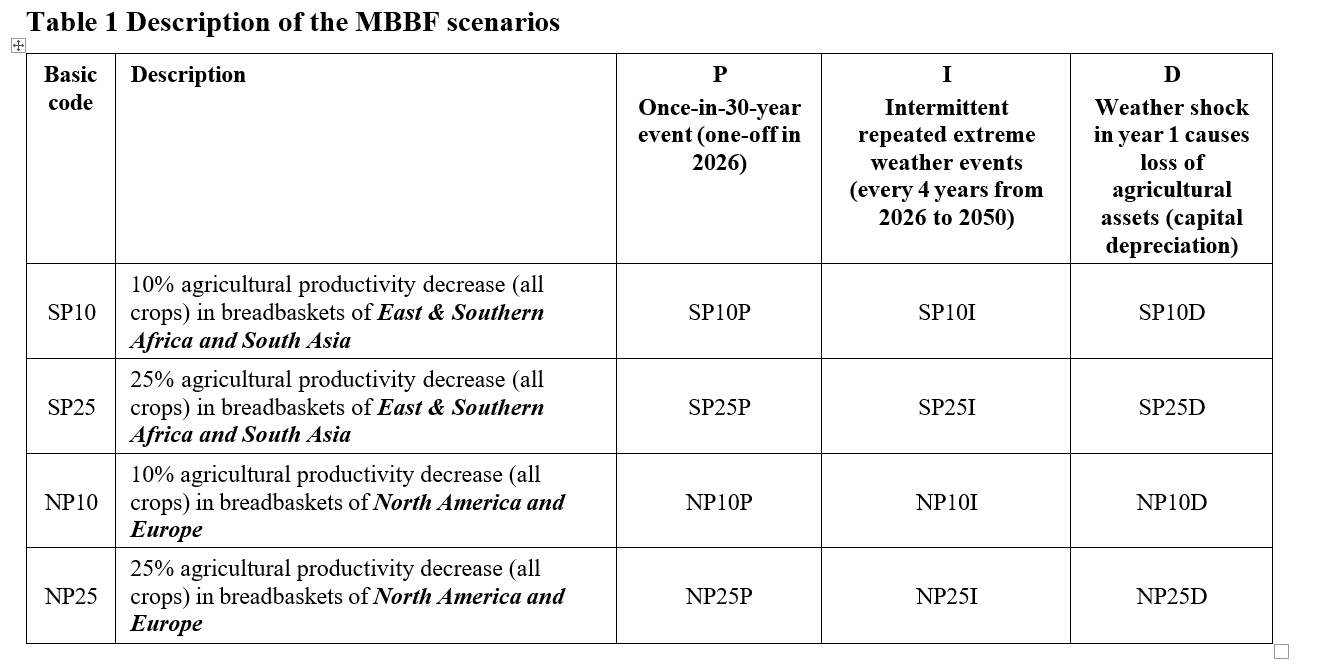

In our paper, we compare the global ramifications of two hypothetical multiple breadbasket failures caused by extreme climate events in different regions. The first examines extreme weather shocks in Southern and Eastern Africa and South Asia. The second analyzes the impacts of MBBFs concentrated in North America and Europe. For illustrative purposes we considered crop yield declines in the affected regions of 25% for all crops. We estimate the ex-ante ramifications of such a scenario using IFPRI’s global MIRAGRODEP model, which is well-suited to assess the transmission of agricultural productivity shocks through local and global market channels and implications for household incomes and food security.

MBBF scenario

This study examines Major Breadbasket Failure (MBBF) scenarios to understand how global food security and markets would respond depending on where the failure occurs in high-income regions or in low- and middle-income regions.

Results

1. Effects on Macroeconomics

Source: Martin, Will; Nia, Reza; and Vos, Rob. 2025. Global food security impacts of extreme weather events and occurrence of breadbasket failures. IFPRI Discussion Paper 2360. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/176642

Click here for the full screen

2. Effects on Food Prices, Consumption and Diets

Source: Martin, Will; Nia, Reza; and Vos, Rob. 2025. Global food security impacts of extreme weather events and occurrence of breadbasket failures. IFPRI Discussion Paper 2360. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/176642

Click here for the full screen

3. Effects on Farm Sectors

Source: Martin, Will; Nia, Reza; and Vos, Rob. 2025. Global food security impacts of extreme weather events and occurrence of breadbasket failures. IFPRI Discussion Paper 2360. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/176642

Click here for the full screen

4. Effects on Poverty and Food Security

Source: Martin, Will; Nia, Reza; and Vos, Rob. 2025. Global food security impacts of extreme weather events and occurrence of breadbasket failures. IFPRI Discussion Paper 2360. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/176642

Click here for the full screen

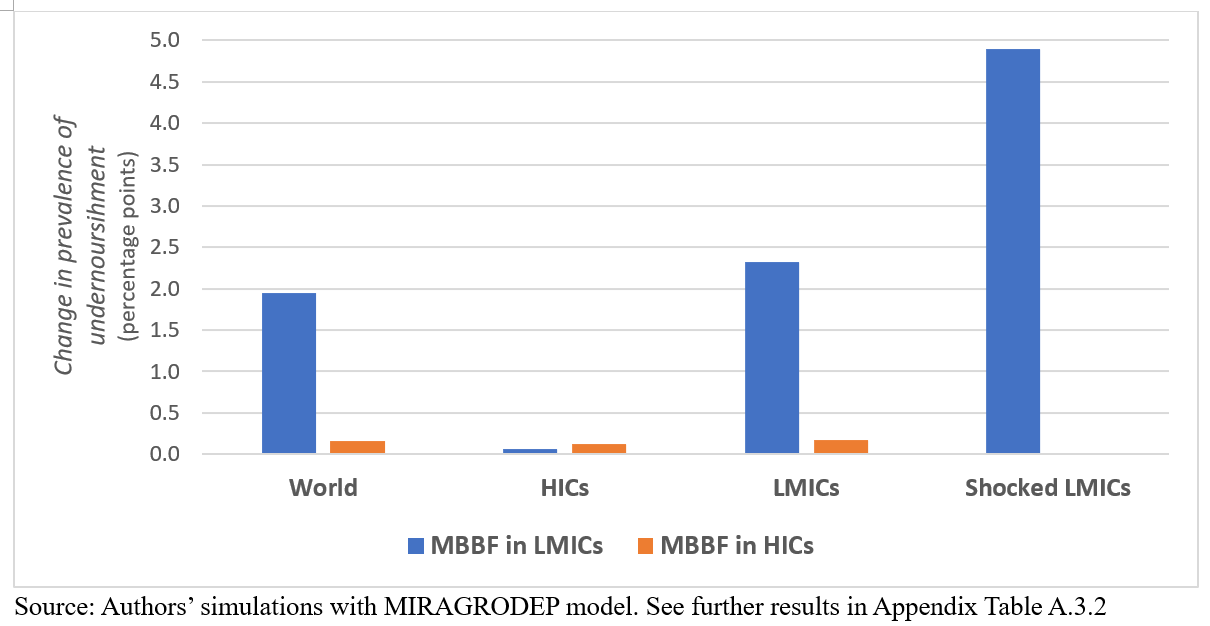

Food security impacts of MBBFs in high-income countries differ from those in developing countries

Our findings show that MBBFs can lead to substantial increases in global food insecurity and poverty. They also show that these shocks are dramatically more serious if they occur in developing countries where many people are vulnerable to poverty and food insecurity.

An MBBF causing a 25% loss in yields in Eastern and Southern Africa and South Asia would cause an estimated 2 percentage point increase in the global prevalence of undernourishment (compared with the baseline), affecting 160 million more people. In the affected regions, food insecurity could increase between 4 and 10 percentage points, as farm households are hurt by lower output and incomes and other vulnerable households by sharply rising food prices.

Simultaneous shocks to production in the high-income countries in Europe and North America will have large impacts on global staple food prices that indirectly affect households in poor countries. However, we find that these impacts would be much more serious if the extreme weather hits production areas in low- and middle-income countries.

An MBBF in North America and Europe would cause a bigger fall in global incomes and a larger increase in world food prices, as a result of their large weight in the global economy and in international trade. The impact on global food security and poverty would be much more muted, with farm incomes rising in most developing country regions. Countries in Eastern and Southern Africa, however, with many net buyers of food, however, would suffer more poverty and food insecurity in this scenario.

Figure 1 Comparison of food insecurity impacts of MBBFs in HICs and LMICs in the year of the shock, % points

Food systems can rebound rapidly, but lasting damage may remain

A natural disaster may not just cause a temporary decline in agricultural production but sustained reductions from loss of physical and human capital. These losses are perhaps most obvious with livestock grazing systems where livestock inventories can be severely depleted during droughts. Droughts, floods and fires may also cause physical loss of physical and natural capital such as water management systems, buildings, fruit trees and standing timber.

Such capital losses, especially when associated with MBBFs in developing-country regions would exacerbate the impacts on global poverty and food insecurity. Yet, permanent losses may be limited even in these scenarios, if subsequent recovery of agricultural production and gradual recovery of agricultural capital stock

Policies

Our analysis has not, as yet, considered policy responses. Popular responses to adverse climate shocks in the past have included reductions in tariffs on food products in importing countries and the imposition of export bans in shock-affected producer countries. Such responses have exacerbated the magnitude of global food price shocks and further increased price volatility, and worsening food security. In follow-up research, we plan to assess the effects of such trade policy responses, as well as of domestic price insulation measures to inform policy makers of what anticipatory measures would effectively protect the food security of vulnerable populations against global market shocks driven by extreme weather.