The struggle to get food aid from Egypt to Gaza: Insights from the Egyptian Food Bank

The Gaza Strip has entered a “worst case” food crisis, with its population now facing famine, according to a July 29 Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) alert. Responding to growing international outrage over the emergency, two days earlier, Israel said it was reopening humanitarian aid corridors—allowing international organizations to resume convoys—while the Israeli Defense Force announced a daily “tactical pause” on operations in densely-populated Gaza City, Deir al-Balah, and Mawasi to facilitate aid distribution.

However, it is unclear how effective these moves will be; aid agencies continue to highlight the restricted flow of food trucks across the border. Some countries have started airdrops to bypass the border controls. Yet each airdrop carries less than half as much food as a single truck and can cost seven times as much. The efficient flow of food trucks—which cross at two points along the Egyptian border—is now crucial to relieving the crisis.

The current situation is only the latest and gravest phase of an ongoing humanitarian crisis dating to the start of the Israel-Hamas war on October 7, 2023. Food prices have recently spiked to the highest point in nearly two years of war. Humanitarian organizations have raised urgent concerns in recent weeks about the increasing numbers of children suffering and dying from acute malnutrition due to the prolonged blockade. With continued pressure on dwindling supplies, hunger will increase. The scale of suffering reflects the longstanding, constantly shifting set of obstacles to delivering food assistance from Egypt into Gaza.

The Egyptian Food Bank (EFB) is a key player in this effort. It is an impact-driven NGO established in 2006 to address food insecurity in Egypt. As the crisis in Gaza unfolded, EFB joined in a collective effort of NGOs, called for by Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in October 2023, to deliver food aid, supplying both water and food trucks carrying boxes containing rice, sugar, pasta, fava beans, lentils, flour, ghee, oil, sauce, jam, and cheese. As the crisis has intensified since then, EFB’s experience offers a window into the struggle to combat famine in Gaza.

Gaza blockades and food aid

Gaza has been dependent on outside aid since 2007, when Israel declared a blockade in response to Hamas seizing power. Israel has controlled anything entering the Strip—including essential items such as food, medical supplies, and clothing. Disruptions in the inflows of both humanitarian aid and commercial goods have severe impacts on food security.

The most efficient way for aid to enter Gaza is via trucks from Egypt, with which it shares a 12 km border. Before the Israel-Hamas war, approximately 500 trucks, including both aid and commercial vehicles, were entering Gaza per day from Egypt, each carrying between 18-30 metric tons (MT) of food and other supplies.

In the wake of the October 7 Hamas attacks, Israel tightened the longstanding blockade on Gaza as it waged war, sparking a series of rolling food crises as aid flows were limited and at times halted. In March 2025, Israel completely suspended aid inflows as it ended a three-month ceasefire with Hamas; beginning in May, it allowed limited aid in through the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF), a United States organization backed by the Israeli government and unconnected to other international aid groups. Along with other Egyptian and international NGOs, the Egyptian Food Bank was blocked from sending any aid to Gaza from March until August 3.

Israel has said that this new aid distribution system is aimed at preventing Hamas from interfering with aid distribution and stealing supplies. However, the rate of food distribution has fallen far short of Gaza’s needs. Food deliveries under the GHF system in June and July were only 38,000 MT and 33,000 MT, respectively, compared to 164,000 MT and 216,000 MT in January and February. The system has also proven extremely dangerous: Since May 27, at least 1,000 Gazans have been killed by Israeli forces while attempting to access food aid, according to the United Nations.

Rising food prices

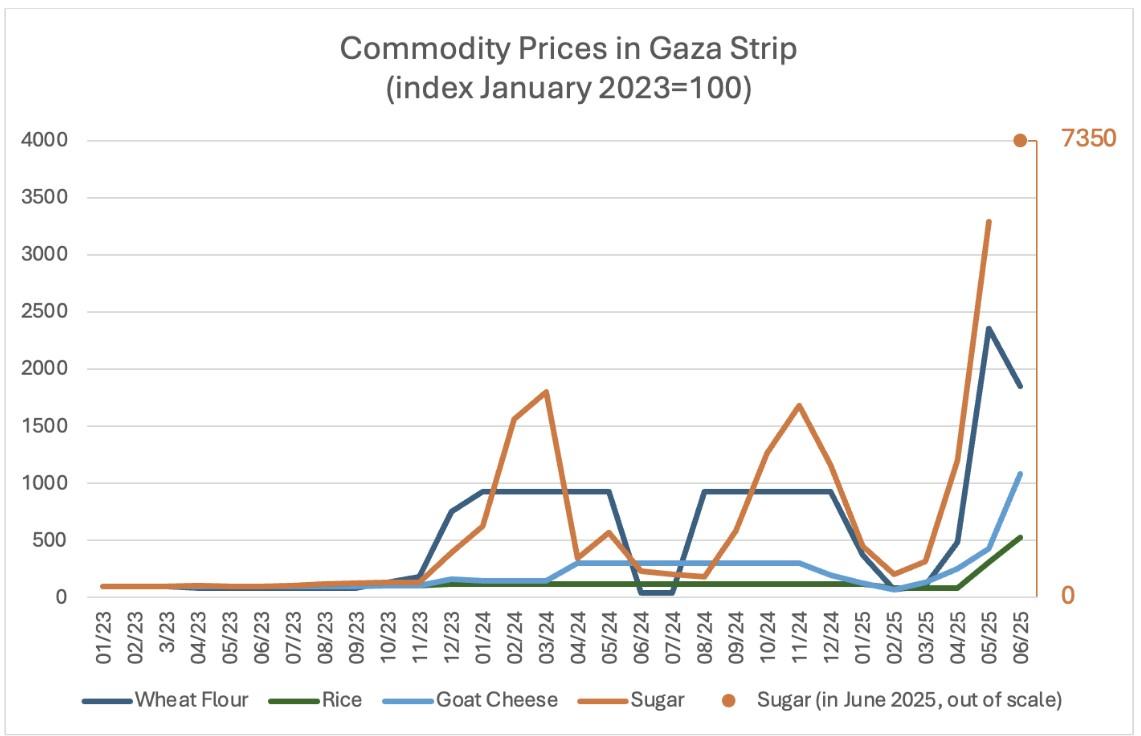

With food supplies shrinking, prices of key commodities have spiked to their highest levels since the war began, according to World Food Programme (WFP) data (Figure 1). As of June 2025, rice was being sold at five times, cheese at 10 times, wheat flour at almost 19 times, and sugar at 70 times their January 2023 price levels. All food items tracked had prices that are more than double the level seen in previous periods of constrained inflows, pointing to severe shortages.

Previous price jumps have corresponded with periods of reduced food inflows. Prices have dropped once restrictions on aid were lifted: In summer 2024, after Israel relaxed border controls in response to heavy international pressure, and in early 2025 during the three-month ceasefire.

Figure 1

Source: World Food Programme

Fluctuating aid deliveries

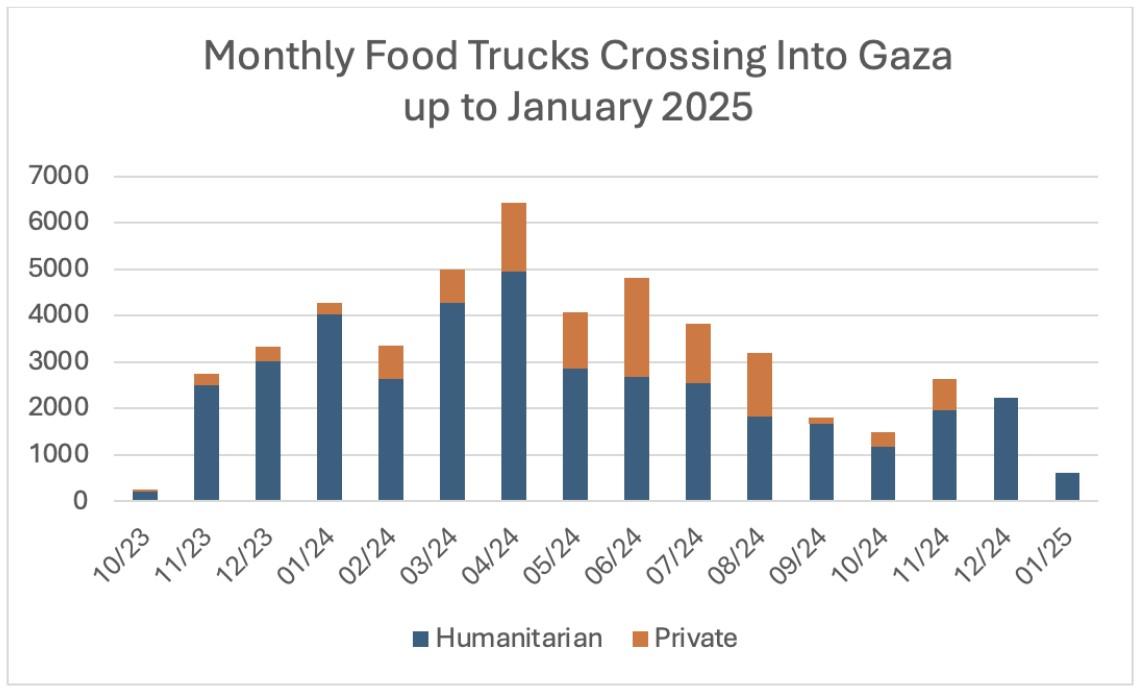

How did the crisis reach this point? Data from the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), the Palestinian refugee relief organization (Figure 2), shows that aid deliveries ramped up steadily in the first six months of the war, then started falling in late April-May 2024 and never recovered. Note that private commercial deliveries are under-reported as they were not fully tracked by the UN after April 2024. The volume of commercial trucks increased significantly in summer 2024, though this is not visible in the data.

Figure 2

The Egyptian Food Bank’s challenges

EFB has faced many obstacles to delivering needed assistance. Supplies are not a problem: EFB can deliver far more food than it has been able to. The problem is getting the food to the people who need it.

Before the March aid suspension, the process for getting trucks across the border and assistance to people who needed it was extraordinarily cumbersome.

Before loading the trucks, EFB had to adhere to very stringent and unnecessarily complicated packaging specifications and material restrictions set by Israel. On many occasions, convoy workers were required to unload and repack the food pallets for no apparent reason. Trucks were required to wait in queues lasting up to several weeks. Trucks then proceeded to the Kerem Shalom crossing, where it could take another few days for inspection and release into Gaza. Once inside Gaza, trucks passed through multiple checkpoints and traveled on roads that were often blocked, damaged, or otherwise impassable. There were no clear rules about the types of aid allowed, and EFB had to learn by trial and error what was allowed. For example, infant formula and cookies were sometimes blocked and sometimes allowed after appeal.

EFB had raised enough money for a major relief effort, but only a fraction of the trucks that it could have sent into Gaza were allowed to deliver food. By June 2024, the border restrictions were loosened, commercial trucks were allowed through, and delays shortened.

While Israeli officials have explained the ever-shifting border control regime as necessary to prevent Hamas interference, EFB leaders see the situation of onerous aid inspections and blockages at the border as a political tool intended to limit aid deliveries and pressure Hamas—as evidenced by Israel’s willingness to loosen the restrictions in response to international pressure.

Clearing the path for aid deliveries

The constantly changing set of obstacles slowing or blocking aid delivery to Gaza’s suffering population is a major contributor to the current unfolding humanitarian catastrophe. The necessary assistance is available; we need to be able to deliver it to Gazans. On August 3, EFB sent a 25-truck aid convoy that is now heading to the Rafah border crossing; it is still uncertain if the food being carried will be allowed to reach who desperately need it. A political solution is urgently needed that would allow EFB and other organizations to resume efficient deliveries of both food aid and commercial supplies into the Gaza Strip.

Sikandra Kurdi is a Research Fellow and Country Program Leader for Egypt with IFPRI’s Development Strategies and Governance Unit, based in Cairo; Mohsen Sarhan is CEO of the Egyptian Food Bank; Ali Abdelhadi is an IFPRI Senior Communications Specialist based in Cairo. Opinions are the authors’.

The Egyptian Food Bank is the largest NGO in Egypt working on in-kind food distribution and has partnered with IFPRI in the design and implementation of impact evaluations and on seminar series advocating for evidence-based programming.