Realistic options for repurposing fertilizer subsidy spending

Worldwide, government spending on subsidies in agriculture, fishing, and fossil fuels amounts to a staggering $1.25 trillion annually. Subsidies play a significant role in every country’s fiscal policies, regardless of income level or spending patterns. Spending on energy and agricultural subsidies consistently accounts for 2%-3% of GDP on average across income levels and make the production and transportation of food cheaper.

Spending on these subsidies is coming under increasing scrutiny as governments struggle to mobilize additional revenue to meet important development targets amid rising debt distress, dwindling aid resources, and citizen protests against unpopular tax increases. One solution proposed by a growing consensus of voices—discussed during a CGIAR event at the United Nations 4th International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD4)—is to repurpose expensive subsidies towards expenditures that generate higher development benefits.

While these subsidies aim to address low agricultural productivity, high food prices, and other critical challenges, their continuing predominance in food system investments raises important questions: Is this an effective way to spend public funds on such a large scale? If not, can some of the money currently going to subsidies be used to finance other needed investments (that may in turn make subsidies themselves more effective) and if yes, what type of investments can they fund?

This blog post explores these questions, focusing specifically on fertilizer subsidies, a major source of government support for farmers, especially in low-income countries, where they comprise a quarter of all subsidy spending (as well as one-tenth of such spending on in high income countries).

1. Is fertilizer subsidy spending cost-effective?

Fertilizer subsidies aim to improve agricultural yields by addressing the under-use of fertilizers in farming, a major issue in many LICs, and the main reason those countries spend relatively more on them. The share of GDP going on input subsidies (in most cases subsidies to inorganic fertilizer) is 0.4% of GDP in LICs compared to less than 0.1% of GDP in high-income countries.

Overall, fertilizer subsidies positively impact production, bringing indirect benefits to national economies. However, they are not the most cost-effective way of achieving this objective in the long run. They do not address the underlying constraints driving under-use, meaning they often fall short of the desired impact on production.

When soil health is poor, standard fertilizer packages yield lower returns (see this recent Food Policy special issue). In areas without irrigation, the impact of fertilizer use is weather-dependent, increasing production when rains are good, harming the crop when rains fail. Inefficient crop markets make the output price relative to the price of fertilizer too low even when subsidized. Equally important, highly volatile output prices reduce any farmer’s incentive to invest in fertilizers. In addition, farmers operating in underdeveloped financial markets often cannot purchase complementary inputs or insurance for the production risk they face. Finally, fertilizer subsidies often target specific crops, frequently cereals, thus distorting production choices and market development. In sum, fertilizer subsidies are a blunt instrument to address a complex set of constraints.

Fertilizer subsidies also score quite poorly in other ways. A recent World Bank incidence analysis across countries shows that much of the benefits of subsidy spending go to better-off farmers, and that the subsidies contribute to GHG emissions. Finally, government procurement and distribution associated with subsidies can crowd out the development of private input markets, stifling innovation and market responsiveness.

In sum, current levels of spending on fertilizer subsidies are not an effective use of public investments in food production and trade. We can do better.

2. Why are subsidies so popular?

Nevertheless, fertilizer subsidies remain consistently popular policy instruments for increasing productivity. During crises, governments often increase them to support the agricultural sector, stabilize food prices, and prevent food shortages. For example, many countries implemented new fertilizer subsidies or expanded existing programs in 2022-23 when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine triggered a spike in global fertilizer prices. It is worth taking another look at why governments spend so much on subsidies in the first place, and why those policies persist.

Subsidies have four key features that make them attractive to political leaders, policymakers, recipients, and the public:

- Immediate benefits: Subsidies are effective at increasing input use and boosting short-term yields. This makes them particularly appealing during crises or as tools to address structural food security needs. Moreover, while a non-negligible share of subsidies goes to farmers who are better off, they do benefit many poor farmers, providing much-needed relief.

- Visibility: The public often judges a government’s competence on observed outcomes. Thus, governments lean towards high-visibility goods that constituents are more likely to credit them for providing. Unlike training of extension workers or improving the nutrient content of food supplies—interventions that the public may struggle to see—bags of subsidized fertilizer or e-voucher cards are immediately visible to farmers and their communities. Visibility is particularly valued in contexts where there is low overall trust that the government can deliver other goods and services.

- Private benefits that can be selectively distributed: Fertilizer subsidies are private goods that can be selectively allocated for political reasons. Many studies show that politicians have used fertilizer subsidies to reward co-partisan supporters or to co-opt opponents. In addition, the contracts for procuring and distributing fertilizer can also be selectively allocated to favored companies.

- Simplicity of implementation: Compared to more complex policies such as agricultural research or extension programs, subsidies are relatively easy to implement. They can be quickly rolled out through existing distribution networks and require less regulatory oversight than more complex policy interventions. They do not require extensive training programs or long-term capacity building.

These four features—immediacy, visibility, private benefits, and simplicity—make subsidies popular among both rural populations and governments, making them a mainstay of public spending in low- and middle-income countries. Therefore to be a feasible alternative, any replacement spending will likely need to have these characteristics too.

This presents a challenge to subsidy reform efforts. Some highly cost-effective investments lack these features—and would probably not be good candidates for repurposed subsidy funding.

For instance, spending on agricultural research and development has very high returns, but those come in the long run, are available to many, and have low visibility. Often, studies on potential benefits of repurposing have identified agricultural R&D as the alternative, but the fact that this is a long-run, low-visibility public good investment makes it a very unlikely reform in practice. Similarly, increasing investment in extension services can be effective in boosting yields, but it is difficult to implement, often requiring training of a large cadre of extension workers who must then deliver improved services.

Infrastructure investments, such as investments in railroads, rural roads, electrification, and market sheds, are more visible to the public than R&D or extension services, but they are less amenable to selective distribution to political supporters and take more time to materialize.

While some funds can and should be repurposed to these high-return and transformative investments, clearly not all subsidy spending can be redirected in this way.

3. What are the best policy alternatives for repurposing subsidies?

Realistic policy alternatives should be transformative and also share the immediacy, visibility, private benefits, and simplicity of fertilizer subsidies. What existing programs meet these criteria? This is an area where IFPRI and other CGIAR centers have been working to document successes in innovative subsidy reform (and where there is an ongoing need for more evidence).

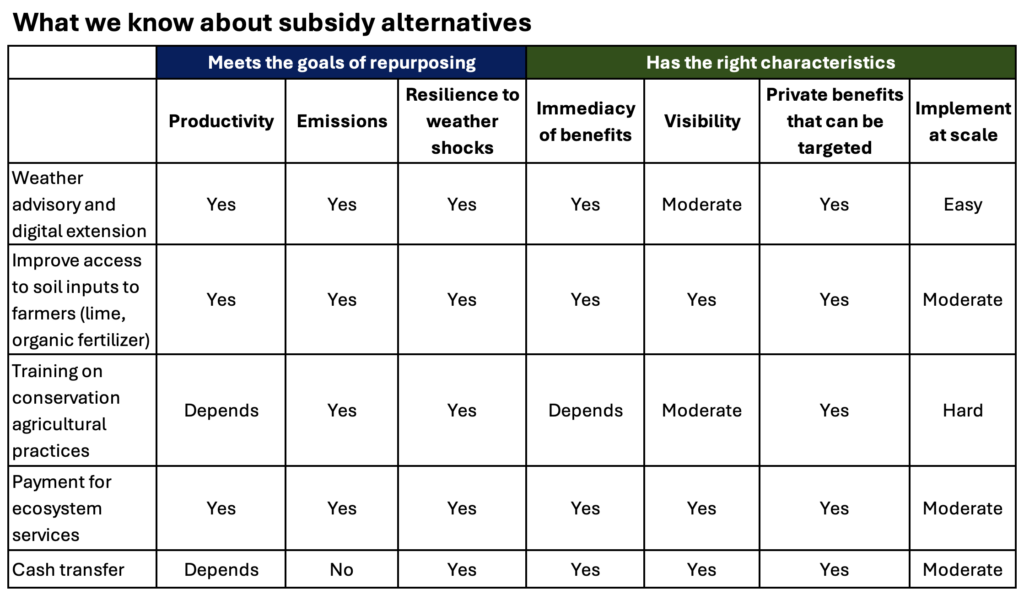

Table 1 summarizes some of the evidence on a set of alternative policy interventions. We highlight four examples here:

- Digital advisory services provide farmers with timely and accurate information to optimize their practices and increase farmer profits. Digital delivery of personalized extension in Nigeria increased farmer profits by 10%.

- Subsidizing soil testing and soil investments promotes sustainable soil management to ensure long-term productivity. In Tanzania, extension agents provided maize farmers with low-cost soil testing, customized input recommendations, and vouchers to pay for inputs needed. Fertilizer application almost doubled and maize yields increased substantially.

- Payments for ecosystem services incentivize farmers to adopt environmentally-friendly practices. They may not have an immediate return (which is why a payment is needed) but have long-run productivity gains. In Ethiopia, cash transfers to households for investing in land management saw tree cover increase by 5%. This and other land management programs increased productivity by 13.5% in places experiencing severe drought.

- Small-scale irrigation enhances water management with an immediate impact on productivity in many places and helps build resilience against climate shocks in the long run. Such investments are often constrained by a lack of long-run finance options, providing a role for public support.

These investments are transformative, offer immediate and tangible benefits to farmers, and can be implemented with relative ease.

Table 1

Conclusion

When fertilizer subsidies make sense and are well-designed, there may be a case for spending on them, but much of the funding they currently receive around the world can be redirected towards more transformative investments.

For that effort to work, those investments must share key characteristics of existing subsidies—especially to anticipate likely political opposition. More evidence is also needed on how to roll out alternatives at a national scale and how to sequence that with the withdrawal of fertilizer subsidies.

Ruth Hill is the Director of IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions (MTI) Unit; Danielle Resnick is an MTI Senior Research Fellow and a Non-Resident Fellow with the Brookings Institution’s Global Economy and Development Program. Opinions are the authors’.