When Policy Responses Make Things Worse: The Case of Export Restrictions for Agricultural Products

When the global prices of staple commodities surge, some governments react immediately by imposing trade-restricting measures in order to insulate domestic prices from rising world prices. During the global food price crisis of 2007–2008, such behavior was observed among many governments, particularly in net food-exporting countries, in response to the impending food security shock. As many as 16 countries imposed some form of export restriction, such as a ban or export tax, on commodities including rice, wheat, maize, other grains, and vegetable oils. In February 2022, as the world was returning to normal after the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ukraine-Russia conflict again sent food security shock waves across the globe. Russia and Ukraine together account for 12 percent of the total calories traded globally (Glauber and Laborde, 2022), and the ongoing conflict severely disrupted that trade. In response, as many as 28 countries have put restrictive measures on a range of products, including food and fertilizers (Laborde and Mamun (2022).

Countries’ use of export restrictions is similar to that of import tariff increases: both improve the country’s terms of trade, influencing the world price in their favor (Bouët and Laborde, 2010). This rationale works well when a country has a very large share in the world market for a specific commodity.

On the other hand, when a country has low food stock, concerns about food availability and price stabilization in the domestic market are the major drivers for governments to undertake various export restrictions. During 2006–2008, many countries, including Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, and Pakistan, adopted such policies amid growing fear of price surges for crucial products including wheat, rice, and palm oils. These countries either implemented a complete ban on exports of commodities or used variable tax rates to limit exports.

What trade patterns do we observe during different episodes of export restrictions?

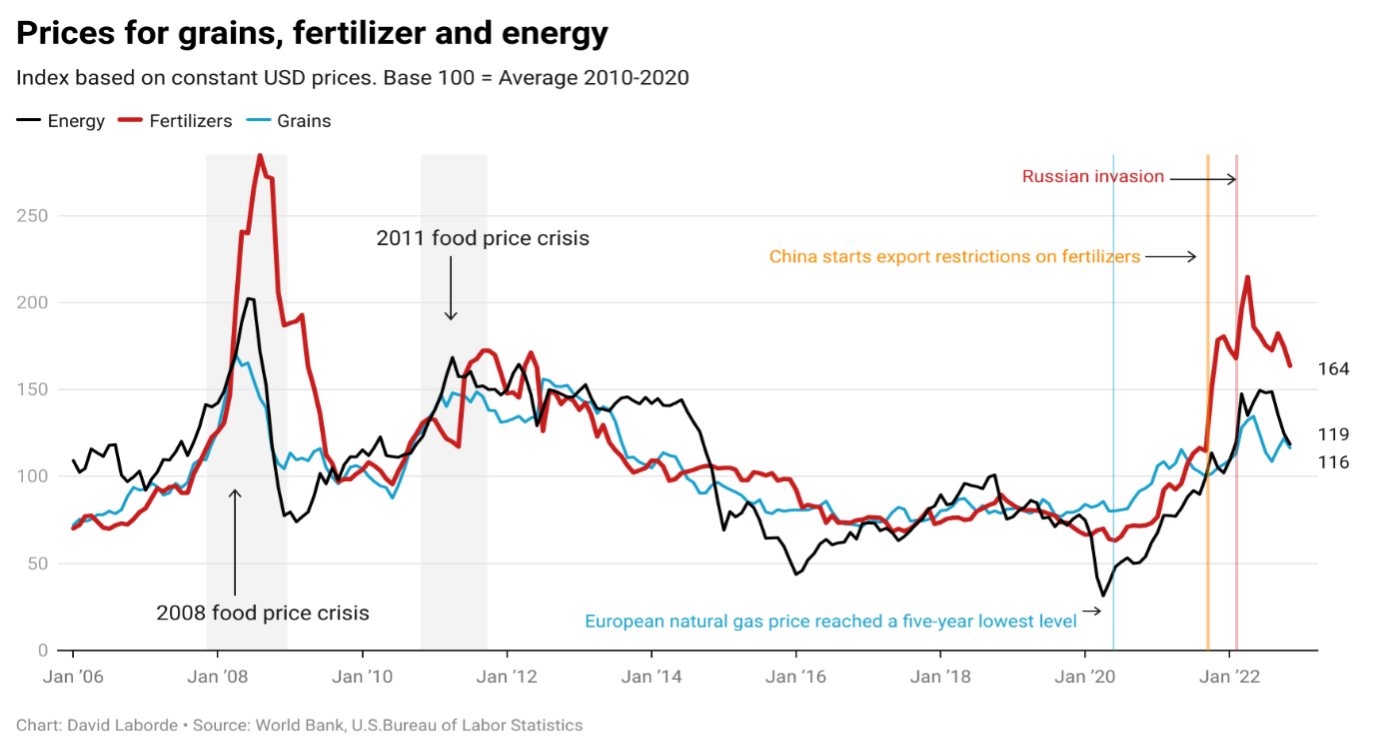

As is evident from Figure 1, which presents the price movement of grains, fertilizer, and energy and the recent episodes of export restriction, price fluctuations play a key role in triggering export restriction. A rise in grain prices makes governments nervous, especially in developing countries, as they become concerned about the food security of a large population. When export restrictions of all the major episodes of food price crisis were placed in a time profile (weekly in this case), we observed a quick succession of implementation of new measures over a short period, with too many countries attempting to block exports, which has a cascading effect (Bouët and Laborde (2010).

While export restrictions destabilize markets and contribute to price fluctuations, they vary greatly in terms of intensity. The 2008 global food price crisis brought shocks to many food-insecure countries as they struggled to find alternatives for importing food. The current Russian invasion has placed many countries in Africa and Asia in a much more vulnerable position, as they were just starting to recover from COVID-19 and the related supply chain disruptions. Wheat, rice, palm oil exports dropped significantly in both 2008 and 2022, while reductions were less significant during the 2010-11 crisis. The COVID-19 case was a mix of both supply and demand shocks, with many poor worldwide becoming jobless and facing severe food insecurity.

How predictive are food inflation and world prices?

Predicting export restriction requires both theoretical and empirical consideration. Price and other economic and demographic indicators play a role in the imposition of export restrictions. We have used a simple probit model to explore whether price, along with key control variables, has predictive power on export restriction. We considered the overall food inflation rate and the world price change of commodities and constructed a database covering all major episodes of export restriction.

The regression model has suggested that the domestic food inflation rate has higher predictive power over export restriction than does a commodity’s world price change. With a one standard deviation increase in the food inflation rate, the probability of export restriction increases by 37.8% when the model is fitted with short-term price change at the global level and considers only price variables. Food inflation captures various factors because it reflects not only the sensitivity of consumers to specific food items but also several structural elements (i.e., institution, stability macroeconomics, level of complexity of the food system) that create an idiosyncratic situation at the country level.

The result changes when control variables, such as trade share in GDP, population density, and per capita income, are introduced; in this case, food inflation as a whole is not a key driver of commodity-level policy responses, but the price changes on global markets of specific commodities are positively associated with export restriction in both short- (3-month price change) and long-term (12-month price change) price movement. In other words, a 1% price rise will increase the probability of a country implementing a restriction on this product by 1%. Among the control variables, trade share, which indicates a country’s trade exposure, has a large influence on the decision to impose a restriction. On the other hand, per capita income was found to be negatively associated with export restriction, meaning that high-income countries have a low probability of export restriction and low-income countries have a high probability.

Most trade literature and empirical studies argue strongly for trade coordination whenever a global food crisis emerges. Our study investigated the factors that trigger export restriction and assessed their forecasting power. With the help of a wealth of data on export restriction coverage, we find that food prices at both domestic and global levels have a large influence on export restriction. This information can help policymakers, and the agencies responsible for implementing restrictions, pay attention to key price variables and coordinate with trading partners.

Bouët, Antoine and David Laborde Debucquet (2010). “Economics of Export Taxation in a Context of Food Crisis: A Theoretical and CGE Approach Contribution.” IFPRI Discussion Paper 00994, June. https://www.ifpri.org/publication/economics-export-taxation-context-foodcrisis

Glauber, J., and Laborde, D. (2022). “How will Russia’s invasion of Ukraine affect global food security”. IFPRI Issue Post. IFPRI, Washington DC. https://www.ifpri.org/blog/how-will-russias-invasion-ukraine-affect-global-food-security

Laborde, D., and Mamun, A. (2022). “Documentation for Food and Fertilizers Export Restriction Trackers: Tracking export policy responses affecting global food markets during crisis”. IFPRI Working Paper 2. IFPRI, Washington DC.