Food export restrictions have eased as the Russia-Ukraine war continues, but concerns remain for key commodities

In the weeks following Russia's invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022, several countries imposed export restrictions—including licensing requirements, taxes, and some outright bans—on a variety of feed and food products. These measures helped to fuel war-related disruptions in global markets and contributed to higher prices and increased price volatility. At the peak of the export restriction trend in late May, almost 17% of global food and feed exports (on a caloric basis) were affected (Figure 1) by measures implemented by 23 countries (numbers similar to those reached during the 2007-08 food price crisis: By the end of April 2008, 19 countries had imposed export restrictions, impacting 15.3% of global trade of calories). After May, many countries partially rolled back the measures: By mid-July, the amount of affected trade had fallen to 7.3%, and largely remained at that level over the rest of 2022, though the mix of affected products changed somewhat over the second half of the year.

In this post, we examine the impacts of these restrictive trade measures on prices, supplies, and other indicators. While the pressures that led to the export restrictions have significantly eased and prices of key food commodities have mostly fallen to pre-war levels, the war continues and markets remain volatile, signaling continuing uncertainty and raising concerns that countries could impose restrictions in the future.

Not surprisingly, countries primarily targeted their export restrictions on the commodities most affected by the war—wheat, feed grains, and vegetable oils. Indonesian limits on palm oil exports, for example, accounted for about one third of all calories affected by such measures, and their May relaxation contributed to much of the subsequent decline in vegetable oil prices. Other grains such as rice have also been affected because of their substitutability. For example, in September 2022, India imposed an export ban on broken rice after exports had risen sharply, driven by high feed grain prices (broken rice is often exported and consumed as a feedstuff).

Figure 1

Export restrictions and the World Trade Organization

Overall during 2022, 32 countries imposed 77 export restrictions in the form of export licensing requirements, export taxes or duties, outright bans, or a combination of measures, according to IFPRI’s Food and Fertilizer Export Restrictions Tracker (Table 1).

The World Trade Organization (WTO) requires member countries to notify it of such measures on a timely basis—but compliance was weak. Of the 32 countries, 26 are WTO members, yet of their combined total of 64 measures, the WTO was notified of only 13 (19%). Of those, 12 notifications were made only after the measure had gone into effect; the average length of time between implementation and notification was more than two months (70 days), and the longest interval was more than eight months (245 days).

WTO members were unable to achieve significant progress on disciplining the use of export restrictions at the 12th Ministerial Conference last June in Geneva. But members did agree to exempt foodstuffs purchased for noncommercial humanitarian purposes by the World Food Programme from such measures.

Figure 2

Impact of restrictions on exports

The impact of any specific export restriction on market prices depends on its severity, timing, and the level of affected exports relative to overall global supplies. Here we consider two such measures that received much attention when announced in April-May 2022: Indonesia’s palm oil restrictions, in force from January to May 2022, and India’s export ban on wheat, which took effect May 13 and continued through the end of 2022 (and remains in effect). In addition, we examine India's September action banning the export of broken rice and implementing export taxes on indica rice.

Indonesia and palm oil

Palm oil exports account for about 58% of the global trade in major vegetable oils (the others are sunflower oil, soybean oil and rapeseed oil). On January 27, 2022, in a move to stabilize rising domestic consumer prices, Indonesia announced it was allocating 20% of its palm oil production for domestic use, more than half of which goes towards biodiesel production. The war in Ukraine followed soon after. It had a large impact on sunflower oil exports (sunflower oil accounts for about 13% of the total volume of vegetable oil traded, and Ukraine accounted for about 50% of sunflower oil trade pre-war). As vegetable oil prices rose following Russia’s invasion, Indonesia announced that it was banning the export of palm oil and palm kernel oil beginning April 28.

Indonesia accounts for about 60% of global palm oil exports—effectively one third of the global vegetable oil market. Vegetable oil prices reacted immediately to the export ban, with Chicago soybean oil futures rising almost 4.5% on the news. But the ban was short-lived. It led to protests from producers, including a large number of smallholders, and the government lifted the ban and other restrictions as of May 22.

The impact of the ban can be seen in Figure 3a. Indonesia palm oil exports in May 2022 total 193,000 metric tons (MT), 92% below May 2021 levels. Once the ban was lifted, exports recovered somewhat but cumulative exports were still down 10% through October compared to January-October 2021.

Figure 3a

Figure 3b

India and wheat and rice

In 2021, India exported 6.2 million MT of wheat, the largest amount since 2013 and far above the 430,000 MT exported per year, on average, over 2016 to 2020. When the war broke out in February, Indian government officials were confident that the country could export as much as 10 million MT to help offset the resulting global shortage. But dryness in the Punjab region cut wheat yield forecasts and on May 13, India imposed a ban on wheat exports. Although India is not a major wheat exporter, the move unsettled global markets, with the Chicago benchmark wheat index rising by nearly 6%.

But the export ban turned out to be less draconian than many had feared. Shortly after the announcement, India said that it would honor all export-related letters of credit and that it would "continue to assist neighbours in their hour of need." In fact, as seen in Figure 2b, monthly wheat exports continued to exceed corresponding 2021 levels until September, when they fell below 200,000 MT; from May through October India exported an addition 2 million MT of wheat. Record high prices have caused increased wheat sowings and with a bumper crop expected in 2023, India is considering lifting its export ban.

In early September, India expanded its trade restrictions, banning exports of broken rice and imposing a 20% tariff on exports of non-basmati rice varieties. India is the world's largest exporter of rice, accounting for over 40% of global exports in recent years. While global rice prices rose throughout 2022, the increases have remained proportionately less than those of other cereals.

Yet these restrictions had only a marginal effect on overall rice trade. While broken rice exports were down by 90% in October compared to year-ago levels, at that point India had already reached a record level of exports for the year. Likewise, the increased tariff on non-basmati varieties had minimal impact on India exports (-2%) for the first two months after the tariffs were put in place. Recent reports suggest that India is contemplating removing rice export restrictions.

Impact of restrictions on prices

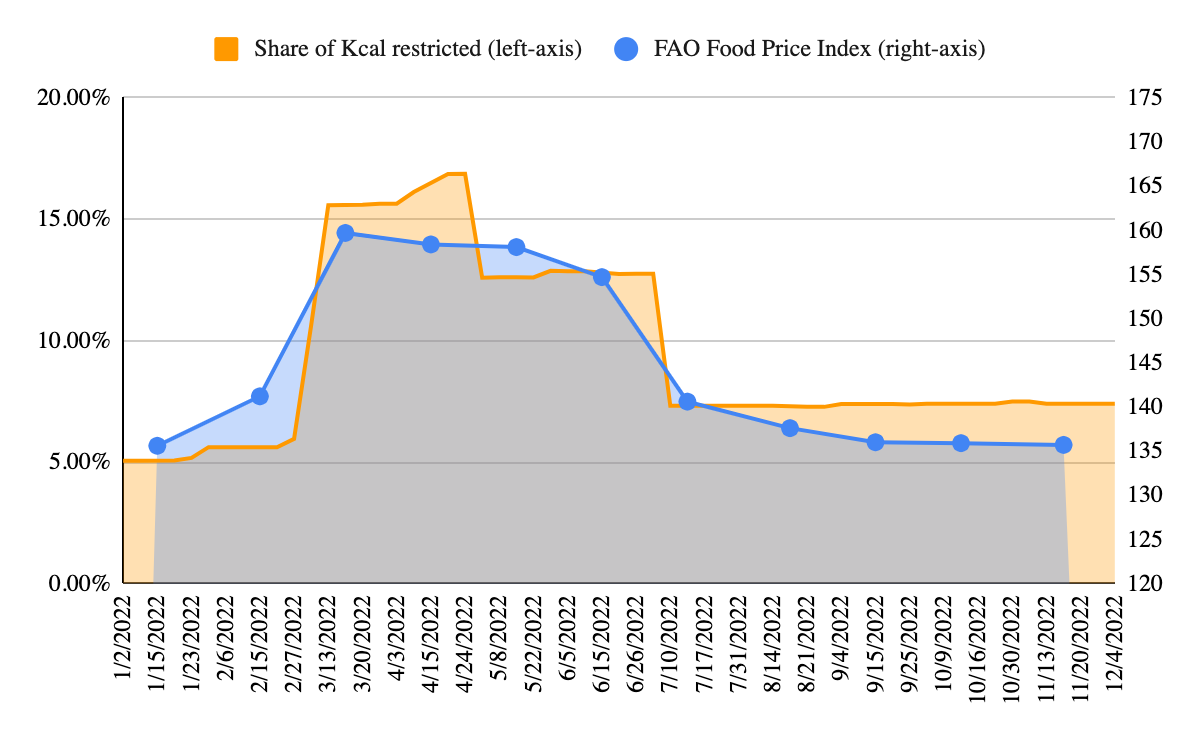

Figure 4 shows the percent of global food trade affected by export restrictions (on a caloric basis) relative to the UN Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) nominal monthly Food Price Index. Though the comparison is largely descriptive rather than analytical, there appears to be a strong correlation between the two series. Prices peaked in May, the same time that over 17% of global trade was hampered by some type of export restriction. Prices then fell from May-July, a period in which some key export restrictions were removed (Indonesia palm oil) or ended up being far less consequential than feared (India wheat).

Nonetheless, it would go too far to ascribe causality here—i.e., concluding that the removal of export restrictions caused global prices to decline. Several other factors have affected global markets, including good summer harvests, and the Black Sea Grain Initiative, which allowed for the partial resumption of exports through Ukrainian ports starting in August. In addition, a drop in global prices can ease domestic concerns and prompt governments to remove export barriers, as we saw throughout the second half of 2022.

Figure 4

Share of global food trade affected by export restrictions vs. FAO Food Price Index

Chart: David Laborde

Conclusions

Almost a year after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, global market prices for key food items have returned to pre-war levels. The war continues, but the share of exports affected by export restrictions has fallen by over 50% from its May peak, while the measures themselves appear to be less consequential than many anticipated.

Nevertheless, it is too early to declare the crisis over. Food prices were on the rise before the war began, and they remain elevated compared to mid-2021 levels. Global stock levels remain tight, and with no immediate prospect for peace in Ukraine and drought affecting parts of South America, prices are likely to remain volatile.

Looking forward, improved crop prospects could help build stocks and dampen price volatility. As with wheat and rice, market tensions on some crops like maize and soybeans have receded and many export restrictions on them have been lifted. But with global stocks tight, poor crop prospects in 2023 could drive prices up again—and push some countries to consider export restrictions. The lessons of 2022, like 2008 and 2011, show that such policies are ultimately detrimental to domestic producers and global consumers, and should be avoided. When imposed, such restrictions should be applied transparently and the WTO notified in a timely manner.

Joseph Glauber and David Laborde are Senior Research Fellows with IFPRI's Markets, Trade, and Institutions Division (MTID); Abdullah Mamun is a MTID Senior Research Analyst. Opinions are those of the authors.