How Can We Lower the Price of Fruits and Vegetables? Exploring Ways to Deliver Vouchers to Consumers

Fruits and vegetables are a key source of micronutrients in diets, and adequate fruit and vegetable consumption can help stave off non-communicable diseases. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that adults consume 400 grams of fruits and vegetables every day. Yet globally, fruit and vegetable consumption often falls far below that target, and research suggests consumption is particularly low in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). A major reason for this is affordability: studies show that to meet either the WHO target or the higher EAT Lancet target, many people would have to spend 30 to 50 percent of their average income on fruits and vegetables. Therefore, finding ways to make fruits and vegetables more affordable is a public health priority in LMICs.

In the broader development literature, there has been a push to benchmark interventions against distributing cash to beneficiaries. While cash transfers are important for poverty reduction, as people have higher incomes the rates of overweight and obesity rise, suggesting that additional expenditures may go toward less healthy foods. Therefore, it is possible that vouchers targeting micronutrient-rich foods underrepresented in the diet may be more beneficial than cash in promoting nutrition-linked outcomes.

As part of the larger FVN (Fruits and Vegetables for Viet Nam and Nigeria) project, we designed a randomized control trial to deliver to consumers vouchers that could be used for specific fruits in local markets in Hanoi, Viet Nam, and Ibadan, Nigeria. The objective of this component of the project was to test the extent to which affordability was a major constraint to increasing fruit and vegetable intakes, and whether receiving vouchers can change consumption habits among consumers. In other words, we want to answer the question: Will consumption habits change after a long period of receiving vouchers? Since we wanted to test change to the affordability of fruits, rather than availability, a design goal of the trial was to ensure that the fruit vendors most commonly visited by consumers would accept the vouchers. In the hope of changing longer-run habits, we provided vouchers for a relatively long time (five months).

For this system to work, vouchers needed to be distributed to consumers and redeemable with a large set of vendors. Moreover, to ensure both vendor participation they needed to be reimbursed relatively quickly, since in both countries informal fruit and vegetable retail is a low margin business, with cash from the previous day’s sales helping vendors pay for purchases from farmers, middlemen or larger markets. Additionally, we wanted to make sure that vouchers could not easily be counterfeited.

To meet these criteria, we came up with a unique solution for each country. In Viet Nam, we initially contracted a delivery company to deliver coupons to consumers on a weekly basis; we worked with medical station staff near markets to redeem coupons quickly for vendors. In Nigeria, we distributed coupons to the randomly selected beneficiaries on a weekly basis as well, but redemption was much different. There, we worked with a microfinance institution called Capital Sage, both on developing a coupon management system and for redemption. Capital Sage provides an interesting repayment method, as their agents circulate in Ibadan, acting as mobile points of sale terminals for basic transactions. logging coupons in the system with their mobile phone, the reimbursement value is transferred to the vendors’ mobile wallets. Vendors can “cash out” their mobile wallets by visiting Capital Sage agents in the market. In both settings, we were able to provide a wide variety of vendors willing to accept coupons in exchange for their produce, meeting the goal of changing affordability without requiring consumers to substantially adjust their purchasing habits.

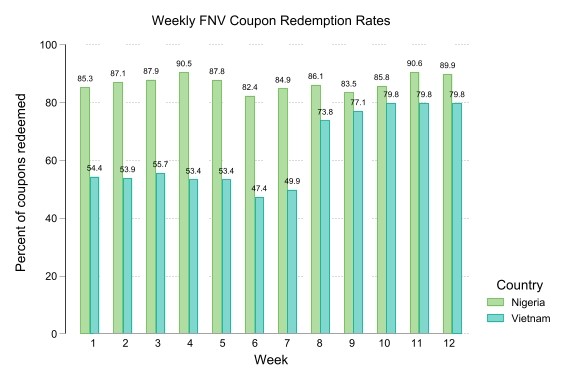

In both countries, coupons appeared to be quite popular as a large share of them were redeemed. Figure 1 shows coupon redemptions for the first 12 weeks of the project.

Figure 1

Consumers in Viet Nam got off to a slower start. In Week 7, our field teams reached out to participants to understand what was hindering their usage and found that deliveries were lagging and unreliable. As a result, we switched to engaging the medical station staff to deliver the coupons, and saw an immediate jump in redemption in Week 8. By Week 12, redemption rates in Vietnam were nearly 80 percent. The data (not shown here) show they are more frequently redeemed in the peri-urban area (Ha Dong) than the urban area (Dong Da), suggesting that lower-income consumers are more likely to use them.

In Ibadan, the coupons were popular since delivery began. Redemption of any given week’s coupons were above 80 percent all weeks and as high as 90 percent.

Of course, coupon redemption does not necessarily mean that households are consuming more fruit; they could be substituting away from normal fruit purchases and buying more of other foods. They could have also used the coupons to purchase higher-quality fruits than they would have otherwise, keeping quantities the same or similar. We hope to answer these questions, and more, with endline surveys being conducted in the 4th quarter of 2021.

Kate Ambler and Sylvan Herskowitz are Research Fellows, and Alan de Brauw a Senior Research Fellow, in the Markets, Trade, and Institutions Division of the International Food Policy Research Institute. Oleyemisi Shittu is Associate Lecturer in the Department of Nutrition and Dietetics at the University of Ibadan.