The future of food demand: Evidence from a global meta-analysis and trend projections

Understanding how food demand responds to income and price changes is essential for anticipating global food needs and expected consumption patterns, and for designing effective food policies. Two key parameters for this are the income elasticity of demand—the percent change in consumption in response to a percent change in people’s income; and the price elasticity of demand—the percent change in consumption in response to a percent food price change. These are essential inputs in a wide range of economic models.

Context-specific food demand elasticity estimates are not always available, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, due to data and capacity limitations. In these settings, researchers and policy analysts often must resort to standardized reference values, such as meta-estimates derived from the combined results of many studies in other countries. However, rigorously estimated meta-elasticities are also rare, often outdated, and mostly food group- or region-specific—rather than being comprehensive.

A new IFPRI Discussion Paper presents our analysis to address this data and knowledge gap. We conducted a global systematic literature review of empirical food demand estimation studies, compiling the most comprehensive global database to date of such estimates, the Food Demand Meta-Elasticity (FDME) database, and identified socioeconomic factors behind heterogeneity in the estimates.

We gathered over 13,000 income and price elasticity estimates from 216 peer-reviewed studies across 57 countries published between 1974 and 2022. We performed meta-regression analyses to quantify how methodological choices, data characteristics, and sociodemographic factors contribute to the significant heterogeneity in observed values. We further estimated meta-elasticities within a unified framework for 206 countries and territories and nine food groups, defined in line with global dietary guidelines. Using these estimates, we built the FDME database. It contains datasets on the full meta-sample, predicted price and income elasticities, and income elasticity projections—providing empirically grounded inputs for simulation models.

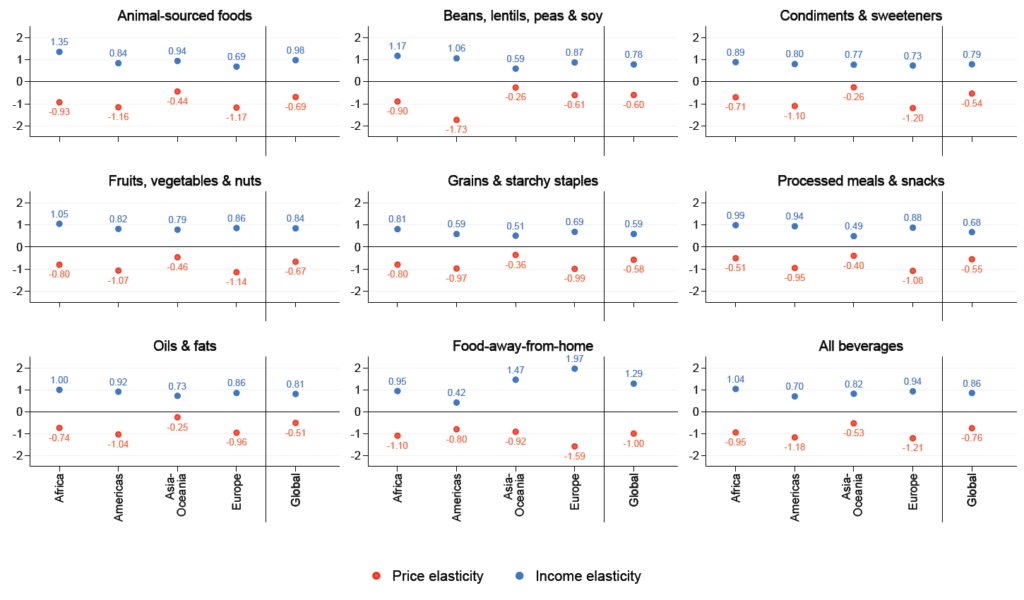

Figure 1. Predicted income and price elasticities in 2021, by region and food group.

What drives heterogeneity in demand estimates?

Our research shows that countries’ sociodemographic characteristics play a significant role in explaining the heterogeneity of demand elasticity estimates. As countries become wealthier, food demand becomes less responsive to income, corroborating the longstanding economic concept known as Engel’s law, which states that households spend a smaller share of their budget on food as their income grows. This relationship is reversed for more discretionary types of food, such as food purchased away from home, for which income growth is associated with higher income elasticity.

While income growth is central to understanding food demand, our study reveals that urbanization and population aging can also significantly alter the responsiveness of food demand to household real income. Urbanization is associated with higher income elasticities, particularly in lower-income countries, where this finding likely reflects increased market access and dietary diversification as people move to cities. However, this effect diminishes as countries become wealthier. Population aging shows the opposite pattern: older populations are associated with lower income responsiveness, consistent with more stable dietary habits and reduced caloric needs among elderly individuals.

Regional differences

Our results also highlight a divergence in food demand trajectories between regions, driven by their differing sociodemographic stages.

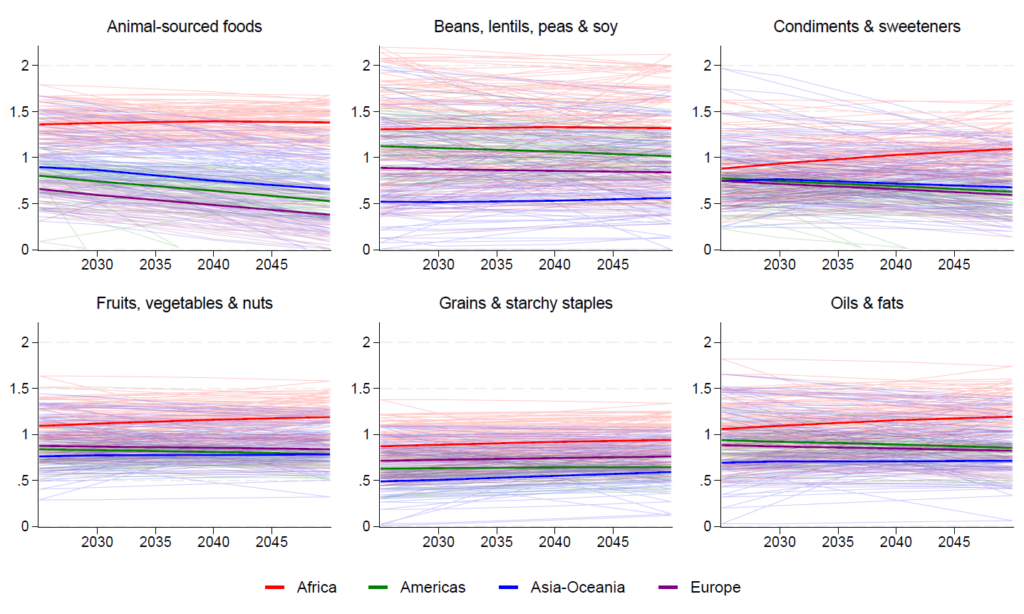

We projected income elasticities through 2050 under five alternative Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs). These five standard global development pathways—SSP1 sustainability, SSP2 “middle of the road,” SSP3 regional rivalry, SSP4 inequality, and SSP5 fossil-fueled development—were developed by the climate research community and are widely used to assess optimistic to pessimistic future scenarios in terms of growth, demography, urbanization, and inequality. They represent a range of plausible scenarios for development, grounded in hypotheses about the key societal factors that most significantly influence the challenges of climate change mitigation and adaptation.

In Africa, food demand remains highly responsive to income growth. As urbanization accelerates in lower-income countries, it improves market access and exposes consumers to new dietary options. Consequently, as income rises, we project continued growth in demand for nutrient-rich foods, such as fruits, vegetables, and animal-sourced foods.

Conversely, in higher-income regions like Europe and the Americas, income responsiveness is declining. This is potentially due to saturation, with consumers already close to their desired levels, as well as population aging.

Figure 2. Projected country- and regional-level income elasticities by food group for the “middle of the road” SSP2 scenario.

The static ‘mistake’

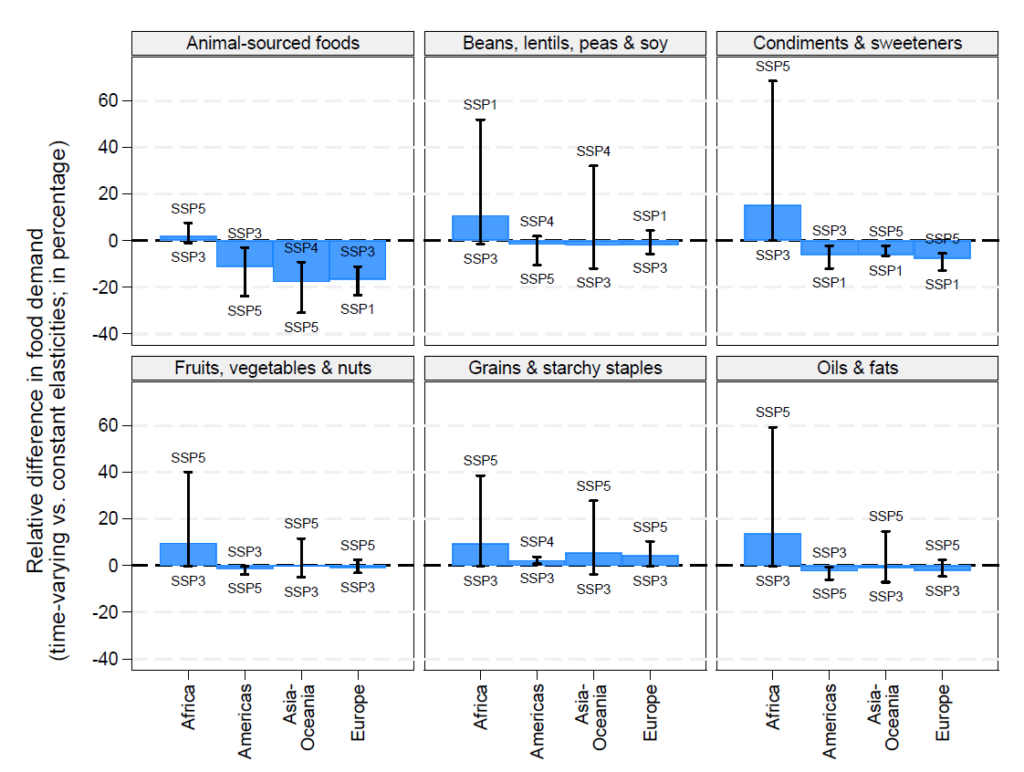

A main finding from our projection exercise is that income elasticities are not fixed parameters; they evolve. Assuming constant elasticities in food system modeling fails to account for saturation effects and sociodemographic shifts.

For example, under the SSP2 “middle of the road” scenario, our projections show that ignoring these structural shifts leads to materially different estimates of future demand. The most striking difference is in animal-sourced foods (meat, fish, dairy, eggs). If we use static income elasticities, we may overestimate future demand. Our dynamic model projects that global demand for animal-sourced foods in 2050 will be 10.7% lower than what static assumptions would predict. In a world grappling with the climate impacts of livestock production, an overestimation of that magnitude could have significant implications for environmental policy and land-use planning.

Figure 3. Relative difference in projected food consumption between the time-varying and the constant 2021 elasticities assumptions, by food group and region, under scenario “middle-of-the-road” (SSP2) and maximum and minimum differences for other SSP scenarios, as of 2050.

Notes: The vertical intervals represent the gap between the minimum and maximum values, and the associated SSP scenarios, for the relative difference in projected food consumption between the time-varying and the constant 2021 elasticities assumptions in 2050.

Looking ahead

Demand elasticities result from underlying preferences. As economies grow and populations become older and more urban, those preferences shift. We can build better models to anticipate the world’s food needs and the impacts of economic shocks and policies by acknowledging that future consumers will not behave like their predecessors. Our database of projected elasticities at the regional and country level under various climate and socioeconomic pathways provides a new tool for researchers and policymakers to do precisely that.

Maxime Roche is a PhD Candidate in the Centre for Health Economics and Policy Innovation, Department of Economics and Public Policy, Imperial College, London; Andrew Comstock is a Senior Research Analyst and Olivier Ecker is a Senior Research Fellow in IFPRI’s Foresight and Policy Modeling Unit.

This work is part of the CGIAR Program on Policy Innovations and was previously supported by the CGIAR Research Initiatives on National Policies and Strategies and on Foresight. We would like to thank all funders who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund.

This post is based on research that is not yet peer reviewed. Opinions are the authors’.