Outline

This tool aims to provide a rigorous framework to assess the risks pandemics like COVID-19 pose to global poverty and food security. It assesses the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on poverty, food insecurity, and diets, accounting for the complex links between the crisis and the incomes and living costs of vulnerable households.

Key elements are impacts on labor supply, effects of social distancing, shifts in demand from services involving close contact, increases in the cost of logistics in food and other supply chains, and reductions in savings and investment. These are examined using IFPRI's global general equilibrium model linked to epidemiological and household models. The simulations suggest that the global recession caused by COVID-19 will be much deeper than that of the 2008–2009 financial crisis. The increases in poverty are concentrated in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa with impacts harder in urban areas than in rural. The COVID-19-related lockdown measures explain most of the fall in output, whereas declines in savings soften the adverse impacts on food consumption. Almost 150 million people are projected to fall into extreme poverty and food insecurity. Decomposition of the results shows that approaches assuming uniform income shocks would underestimate the impact by as much as one-third, emphasizing the need for the more refined approach of this study.

Key finding

The key goal of this paper was to provide a rigorous framework to assess the risks pandemics like COVID-19 pose to global poverty and food security.

Global macroeconomic impacts

COVID-19 will result in a severe global recession with global GDP falling by 5% in 2020.

Poverty impacts

The number of poor increases by 20% (almost150 million people) with respect to the situation in the absence of COVID-19, affecting urban and rural populations in Africa south of the Sahara the most, as 80 million more people join the ranks of the poor, a 23% increase.

Change in diets and impacts on nutrition

The declines in income and supply disruptions are likely to cause quite substantial shifts in demand away from nutrient-dense foods such as fruits and vegetables, dairy products, and meats, and toward basic staple foods such as rice, maize, and other basic grains.

Decomposition of impacts by main drivers

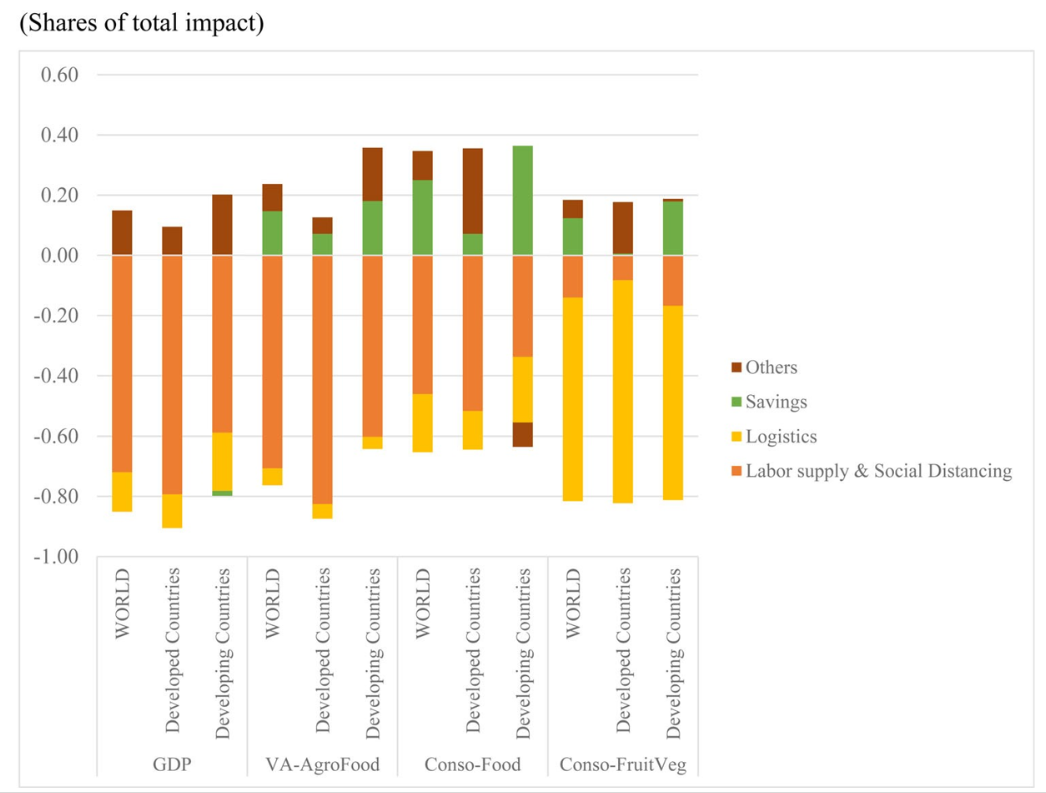

Different shocks have different impacts on the different outcomes, with the direct reductions in labor having the largest impacts on GDP, whereas reductions in saving have important impacts on consumption, and increases in the cost of logistics in food supply chains having the greatest impact on consumption of fruits and vegetables.

Poverty at the global level

The traditional estimate of the poverty impact of the pandemic—the observed changes in real incomes resulting from changes in average nominal incomes and consumer costs—explain most of the changes in poverty. At the global level, these uniform changes explain just over 110 million of the nearly 150 million increase in poverty.

A scenario update

Although the scenarios are broadly similar in terms of the nature of the drivers, the magnitudes of the shocks have been updated and made more country-specific. The aggregate findings of the updated scenario for global poverty are practically unchanged, with the number of poor expected to rise by just under 150 million.

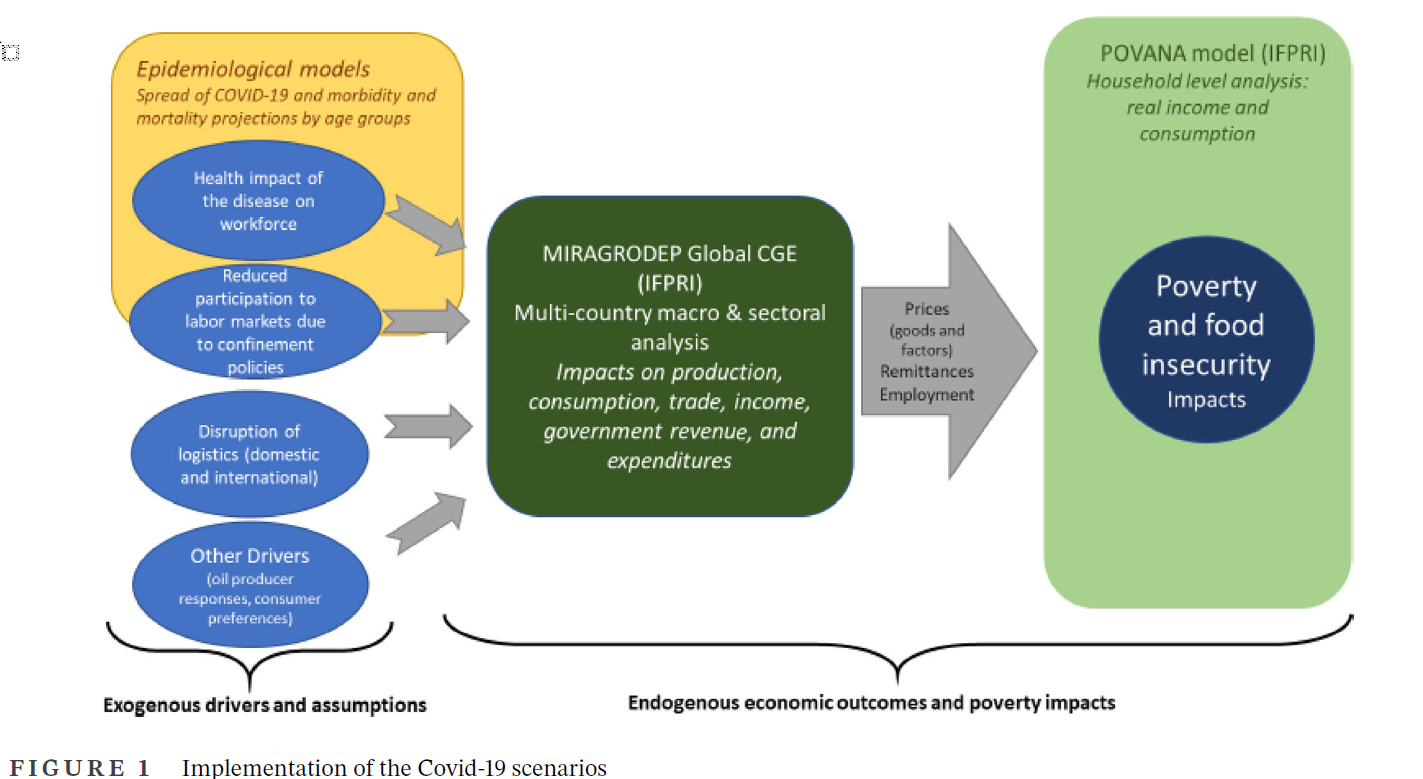

The modeling framework

This tool uses a global modeling framework to assess the potential impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on global poverty and food security. Specifically, it combines two economic modeling frameworks: IFPRI’s global CGE model, MIRAGRODEP, and the POVANA household dataset and model. This framework has been used previously to study the impact of a macroeconomic slowdown on global poverty in Laborde and Martin (2018). The main differences between the cur rent work and the previous study are twofold. First, the Laborde–Martin study looks at a change in economic growth projections for 2015–2030 and compared poverty outcomes in 2030, using the dynamic version of the CGE and projecting household surveys until 2030.

In the current exercise, this tool focuses on single-year (2020) scenario results under a range of assumptions about short-term impacts of COVID-19, as explained further below. Second, in Laborde and Martin (2018), alternative IMF projections for global growth are regenerated by imposing commensurate changes in total factor productivity on the corresponding MIRAGRODEP parameter values. In contrast, in the current exercise, the factors underlying the socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19, such as health impacts, social distancing, restrictions on (labor) mobility, international transport, and the closure of some business activities, are translated into MIRAGRODEP’s model terms to simulate endogenously the impacts on economic growth, incomes, employment, consumption, prices, trade, and ultimately, poverty.

The two modeling frameworks are linked in top-down fashion; that is, the relevant results of the CGE model-based scenario analysis are introduced, along with the direct impacts of the pandemic on households, as shocks to the household survey model to assess poverty outcomes. In addition, the health impacts of the disease on labor supply and productivity are linked to outcomes from epidemiological models. This process is summarized in Figure 1 below.

The COVID-19 scenario

The tool models a range of impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Beyond the direct effects of the disease on the ability to work, income losses arise from people’s desire to avoid catching the disease and their altruistic concerns to avoid infecting other people, and from policy responses designed to reduce the adverse externalities associated with an unmitigated pandemic. No global economy-wide model incorporating these features is available to fully assess these potential impacts and behavioral changes. Many of the changes in behavior and in the functioning of economies are not yet fully understood and their impacts on economic activity were still not fully known when preparing this scenario analysis. It is also difficult to rely on experience from past events, because no events like the COVID-19 pandemic have occurred on this scale in today’s globalized world. Therefore, we have had to make several assumptions about the responses of economic agents to this unprecedented situation.

In crafting the scenarios used here, we have based our choices on earlier work, such as the analysis we undertook in March 2020, when we looked at the differential impacts on productivity and trade costs for a 1% global economic slowdown during 2020. Before looking at the specific scenario assumptions, it is important to keep in mind that the model operates on an annual time step and the impacts of any shock are calculated as the average impact for the year. Therefore, a disruption lasting 10 days is associated with a 10/365 impact and a price shock, for example, such as the decline in oil prices, must be calibrated on the shift in annual average prices and not on the “peak” value.

We distinguish four drivers of COVID-19 impacts: domestic supply disruptions, global market disruptions, household behavioral responses, and policy responses.

Scenario results

Global macroeconomic impacts

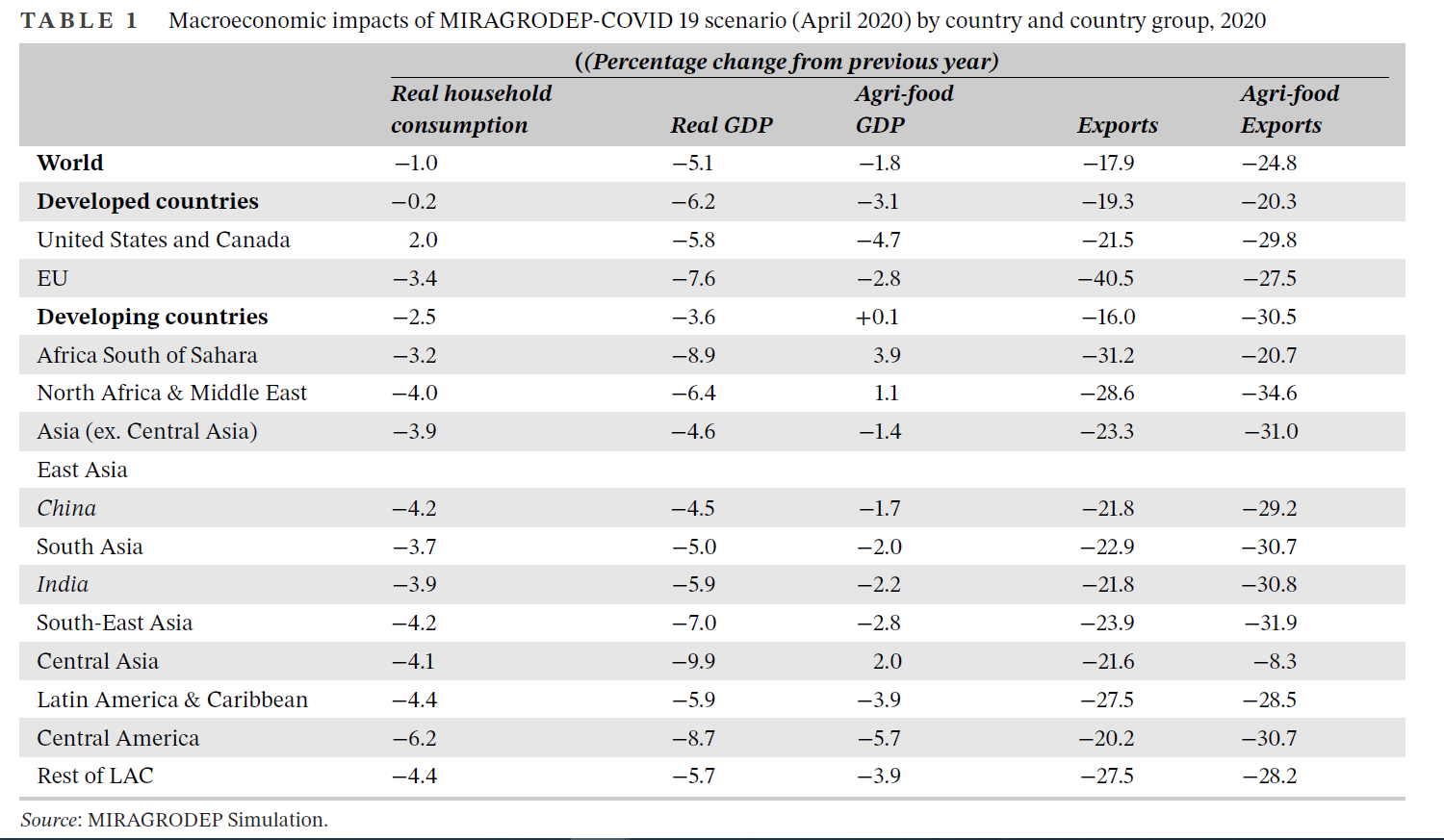

Under the given assumptions, we conclude that COVID-19 will result in a severe global recession with global GDP falling by 5% in 2020*.

This COVID-19 recession looks likely to be much deeper than that seen during the global financial crisis of 2008–2009. The economic fallout in the initial epicenters of the pandemic (China, Europe, and the United States) is also severely hurting net commodity-exporting developing countries through declines in trade and other commodity prices, restrictions on international travel and freight, compounding the economic costs of poorer nations’ own COVID-19-related restrictions on movements of people and economic activity. We consider first the macroeconomic impacts and then the effects on poverty. For developing countries as a group, we project the economic fallout to lead to a decline of aggregate GDP of 3.6% relative to 2019, but economies in Central Asia, Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America would be hit much harder due to their relatively high dependence on remittances, trade, and/or primary commodity exports. The recession is expected to be less severe in China and the rest of East Asia, where—with the present scenario assumptions—we expect the economic recovery to start sooner with the earlier lifting of containment measures.

We expect harsh economy-wide impacts in sub-Saharan Africa with GDP falling on average by almost 9% from the previous year, although agri-food sectors may be spared and could even expand, as the collapse in export earnings and remittance incomes**, with domestic production rising in light of reduced ability to import food push. Lower labor demand in urban service sectors may push workers to return to agriculture, also contributing to greater domestic food production. With more workers in the sector, however, individual incomes would remain low.

* This decline is relative to 2019 levels. Relative to the 2020 baseline (counterfactual without the COVID-19 shock), this implies a 7% decline in global GDP. Only in Table 1, do we present the macroeconomic impacts relative to the previous year (for ease of comparison with other estimates and projections). All other simulation results are with respect to the 2020 baseline (counterfactual without the COVID shock).

** Remittance incomes make up more than 10% of gross foreign exchange earnings in sub-Saharan Africa. In the model, we assume the region’s earnings from remittances drop by 8%. Recent projections project a decline of 9% for 2020 (World Bank 2020c).

Poverty impacts

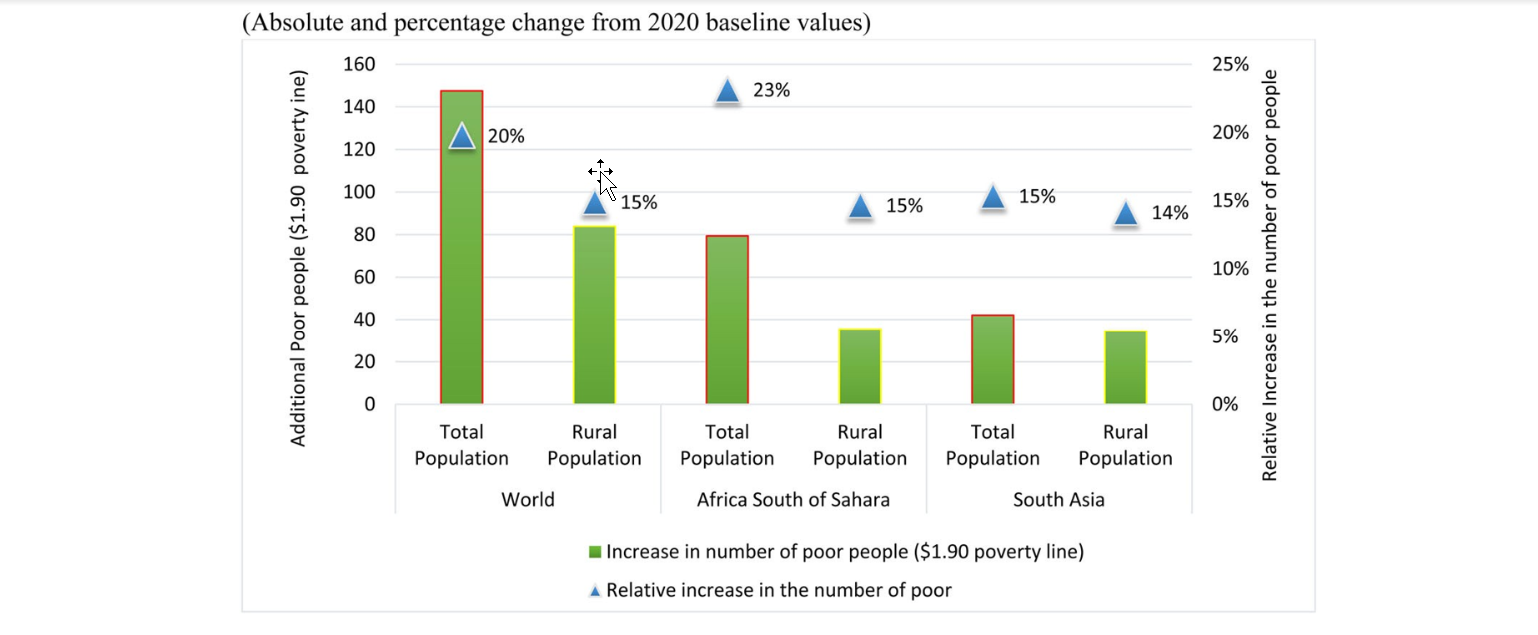

Without social and economic mitigation measures such as fiscal stimulus and expansion of social safety nets in the global South (scenario assumption), the impact on extreme poverty (measured against the PPP$1.90 per person per day international poverty line) is devastating as shown in Figure 2.

The number of poor increases by 20% (almost 150 million people) with respect to the situation in the absence of COVID-19, affecting urban and rural populations in Africa south of the Sahara the most, as 80 million more people join the ranks of the poor, a 23% increase. The poverty increase in rural areas is expected to be smaller than that in urban areas, partly because of the lower rate of transmission of the disease and partly because of the robustness of demand and supply for food relative to many other, more vulnerable sectors. Accordingly, we estimate that, in sub-Saharan Africa, the number of poor people could increase by 15% in rural areas, but as much as 44% in urban areas. In this scenario, the number of poor people in South Asia is projected to increase by 15% or 42 million people.

In both cases, the impacts on rural populations are smaller because the direct impact of COVID-19 on agri- culture is less severe than on other sectors. As these estimates refer to the numbers of extremely poor people, that is, those who typically lack the means to buy enough food, we expect a commensurate rise in the number of food-insecure people. The ability to distinguish the reduced sensitivity of rural households to COVID-19 is an important advantage of the more complex framework used in this study. Applying uniform income declines to the initial distribution of income will almost always result in larger poverty increases for rural people because their initial incomes are so much lower than those of urban residents in developing countries.

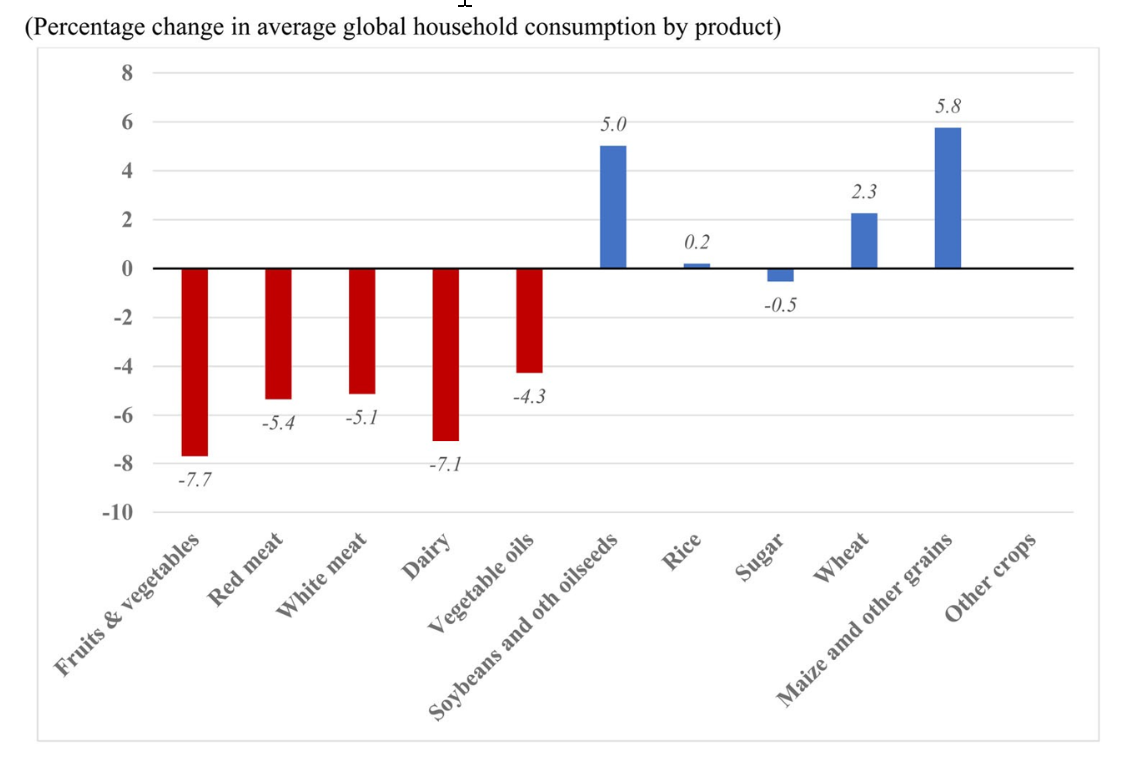

Changes in diets and impacts on nutrition

The income and price changes associated with the pandemic are likely to result in some quite substantial changes in patterns of food consumption, with adverse nutritional consequences. The declines in income and supply disruptions are likely to cause quite substantial shifts in demand away from nutrient-dense foods such as fruits and vegetables, dairy products, and meats, and toward basic staple foods such as rice, maize, and other basic grains. Figure 3 confirms this as a global pattern. The dietary shift is (on average) similar in both developed and developing regions.

Decomposition of impacts by main drivers

Given the multiple shocks used for these simulations, it is useful to understand which shocks influence the simulated outcomes the most. Not only does this provide insights into the driving forces behind both the macroeconomic and poverty outcomes, but also it allows a comparison of our approach relative to the much simpler approach of simply reducing consumption uniformly in line with the decline in GDP at constant prices used by Sumner et al., Mahler et al., and World Bank. The decomposition was done by deleting one shock at a time from the full simulation and assessing the impact of that shock. Adding up these effects provides a good estimate of the total impact and allows a decomposition of the total effect into its sources.

The first three bars in Figure 4 show that the dominant influence on the loss of aggregate GDP due to the pandemic is the reductions in labor supply, both from individual health-related responses and from social-distancing policies.

Disruptions in logistics and the savings adjustment play small to negligible roles in the declines in GDP. The second group of bars shows the decomposition for the impacts on agri-food sector GDP. Again, reductions in supply are primarily driven by reductions in labor availability, although these are less important than for the whole economy because a large share of agricultural value-added is treated as essential. The savings adjustment mitigates the impact on food consumption and hence also on agri-food production.

Income losses owing to the pandemic’s direct impact on people’s ability to work and that of the social distancing measures also explain most of the reduction in total food consumption, compounded by supply disruptions raising the logistical costs embedded in food prices. The savings adjustment is a mitigating factor. The increases in logistical costs affect demand for fruits and vegetables most strongly, outweighing income losses through social distancing; most notably in developing countries.

Figure 4 further shows that the adjustment rule regarding private savings mitigates the macroeconomic impact of the recession on overall household consumption***. The mitigating effect on consumption is generally stronger developed than in developing countries whose, on average, much poorer economic actors have less capacity to absorb the shock by drawing on own savings.

These results show that different shocks have different impacts on the different outcomes, with the direct reductions in labor having the largest impacts on GDP, whereas reductions in saving have important impacts on consumption, and increases in the cost of logistics in food supply chains having the greatest impact on consumption of fruits and vegetables.

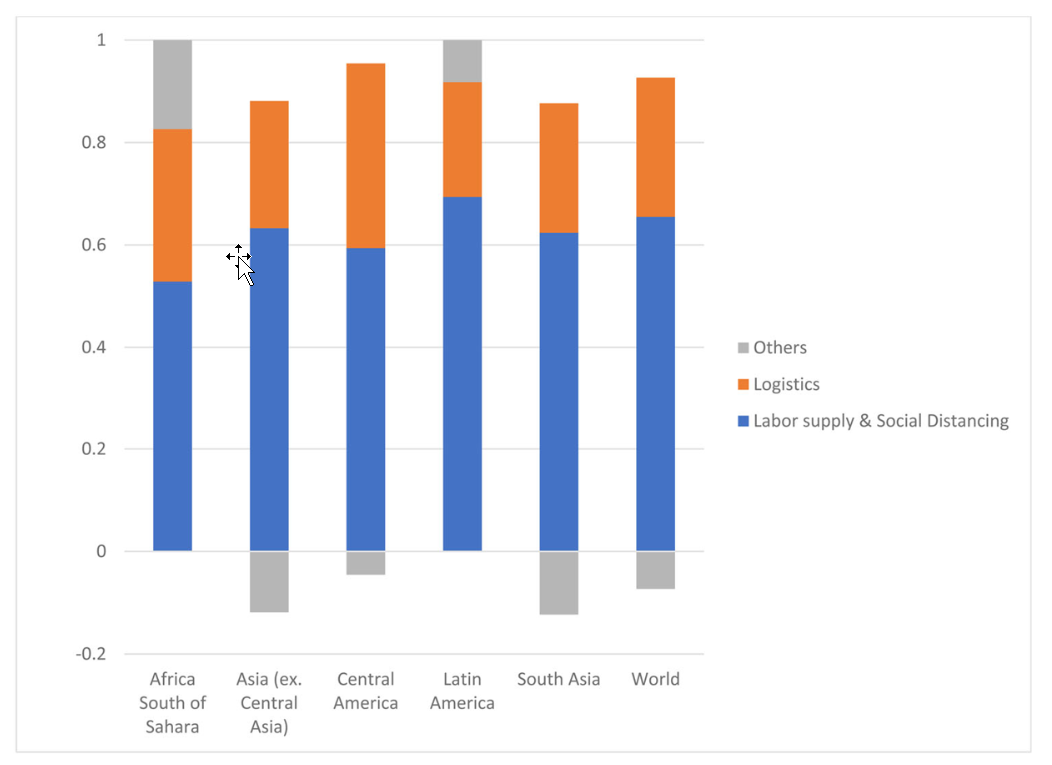

Figure 5 provides a decomposition for the total poverty impacts parallel to that for the macroeconomic impacts presented in Figure 4. Not surprisingly, it shows that the reductions in employment and in labor supply and social distancing have the largest impacts on poverty.

Logistical costs have the second-largest impacts, while other influences, such as oil price changes and changes in savings and investment, reduce the total increase in poverty in several regions.

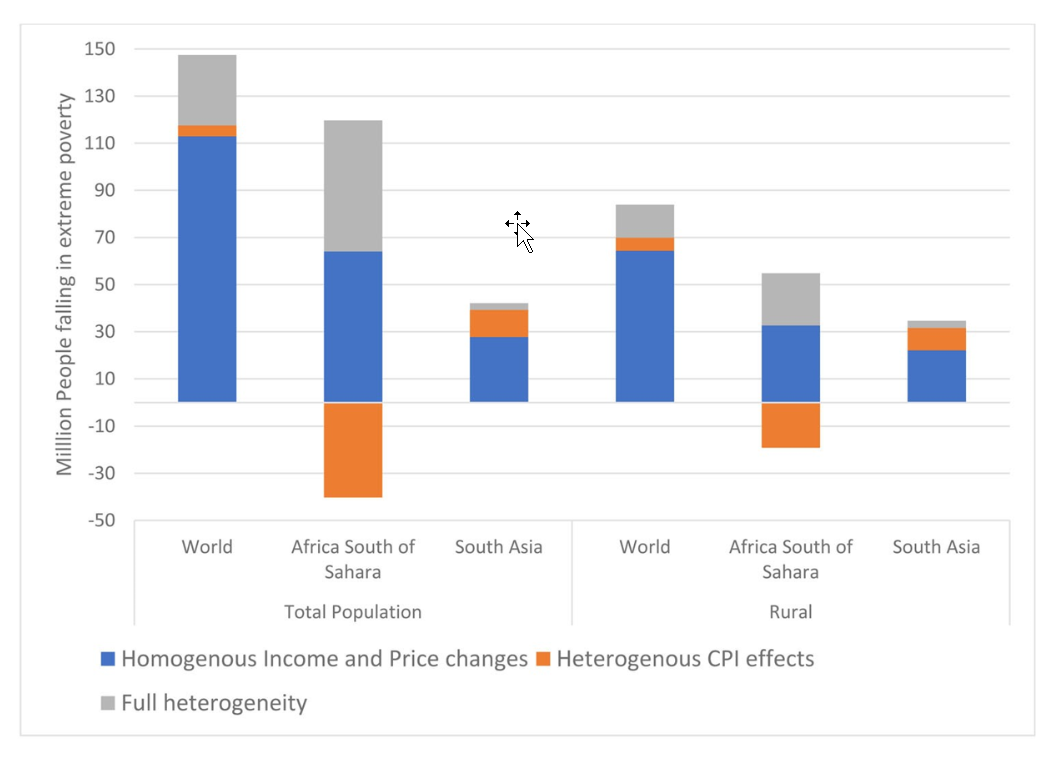

To illustrate the difference between our approach and other studies assessing the poverty impact of the pan- demic, we decompose in Figure 6 the change in the poverty rate into three components.

The first, shown in the blue bar, is the impacts of average changes in incomes and in the cost of living on household real incomes. The second incorporates the nonneutral impacts of the COVID-19 shocks on the cost of living to each household and the consequent impact on household incomes. The third considers, in addition, the nonneutral impact of the shocks on households’ individual incomes. It takes into account, for instance, the fact that many workers supplying unskilled labor—which is assumed to be the situation of the poorest—are unable to work remotely, and hence generally suffer greater income losses than higher income workers, both through the quantity of labor they can sup- ply and the wage rates they receive.

It is clear from Figure 6 that the traditional estimate of the poverty impact of the pandemic—the observed changes in real incomes resulting from changes in average nominal incomes and consumer costs—explain most of the changes in poverty. At the global level, these uniform changes explain just over 110 million of the nearly 150 million increase in poverty. In sub-Saharan Africa, both the uniform income effect and the differential impact on the incomes of the poor raise poverty, but this is substantially offset by many poor people being lifted out of poverty by declines in their idiosyncratic costs of living. This benefit, likely largely driven by declines in farm prices, explains why the increase in poverty observed in Figure 2 is so much smaller in Africa than in South Asia. The pattern for changes in rural poverty follows closely that observed for overall poverty.

*** It is important to point out that the impact on consumption is softened further in the model estimations because GDP is measured in real terms through a Fisher index, while the impact on consumption is measured through a welfare metric (equivalent variation) typically used in CGE models.

Conclusions

Given the multiplicity of links between the pandemic, household incomes, and food security, we concluded that a framework linking economy-wide modeling with household models was needed to capture the impacts of the shock on poverty. We used the MIRAGRODEP global CGE model linked to epidemiological models to capture the impacts on the global economy, and the POVANA household models to capture the impacts at the household level.

The simulation experiments were designed to capture the impacts of the crisis begin with the direct, thus far seemingly minor, impacts of the disease on labor supply resulting from increases in morbidity and mortality. The next key shock was the impacts of social distancing, whether undertaken out of concern about catching the disease or as part of a concerted policy of suppressing the disease—a very important channel of effect with highly specific impacts by sector and type of labor. In addition, we considered the impacts of increases in logistical costs associated with the disease.

Our initial results suggested that COVID-19 would cause a decline in global GDP of about 5% in 2020, with a similar decline in South Asia and a larger decline ( 9%) in Africa South of the Sahara, and much larger declines in global trade because of both increases in logistical costs and declines in investment as consumers and governments seek to reduce the adverse impacts of the crisis on living standards by reducing private and government savings. Consumers are also expected to have shifted their food purchases, buying less nutrient-dense, but more expensive, products such as fruits and vegetables, meat, and dairy products, and buying more calorie-rich and cheaper cereals and processed foods. In an updated scenario, however, using new information about—inter alia—the spread of COVID-19 and related social distancing measures, partic- ularly taking into account the reduced estimates of the spread of the disease in Africa, we expect that the global recession could be steeper than previously anticipated, driven in part by a much stronger economic decline in South Asia.

To better understand these results, we decomposed them by major drivers. The economic consequences of reduced labor supply and social distancing drive most of the impacts on GDP worldwide. Fiscal stimulus in high-income countries and declines in private savings mitigate some, but far from all, the adverse impact on total and food consumption.

The analysis concludes that the pandemic will likely increase the number of people in poverty by about 150 million people, or 20% of current poverty levels. In our reference scenario, most of this increase in extreme poverty was expected to occur in Africa South of the Sahara and South Asia, where many people are currently close to this poverty line. An updated analysis suggests that the increase in poverty may be smaller than originally anticipated in Africa and larger in South Asia, with the global total impact remaining very similar at just under 150 million.

The analytical framework that we use captures many important nonneutralities in the effects of the crisis that are ignored in simpler analyses assuming that all incomes change equally. For example, we find that poverty

increases are likely to be smaller, both in absolute numbers and relative to current poverty rates, in rural areas that are likely less hard hit by the crisis. An analysis of these poverty results suggests that accounting for just the average changes in incomes and in consumer prices would capture only about three-quarters of the total impact of the crisis on poverty rates. Many of the impacts are nonneutral between the poor and the rich and outcomes for the poor are, on average, substantially worse for higher income and more educated people, many of whom can continue to work productively at a distance.

The actual implications of COVID-19 for poverty and food security will depend on a wide range factors, many of which are simply unknown at this point—such as resurgence of the disease during the northern winter and spring, and the efficacy and adoption of potential vaccines. Thus, the results in this paper should not be taken in any way as a precise forecast of the outcome. Rather, the paper provides an approach for evidence-based “what-if” scenario analysis of the impacts of broad-based shocks such as COVID-19 for poverty, food insecurity, and dietary change. As such it should help better understand the relative importance of the multiple channels of transmission and inform policymakers about the socioeconomic consequences of mitigation measures taken to reduce public health risks, and hence, the potential trade-offs between efforts to safeguard lives and those to protect livelihoods.

Partners

The CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions and Markets (PIM)

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation