How Can Food Price Instability be Managed through Trade Policies?

Since time immemorial, fluctuating food prices have been a major concern for populations and policymakers alike, and governments have been faced with the challenge of deciding when and how to manage food price instability. Leaving aside for now the debate about the desirability of price stability per se, I’ll start by recognizing that price stabilization can be managed both with market-based strategies and with public interventions. The latter are more important for our purposes in this series because they often involve trade policies that regulate imports and exports (Galtier, 2013).

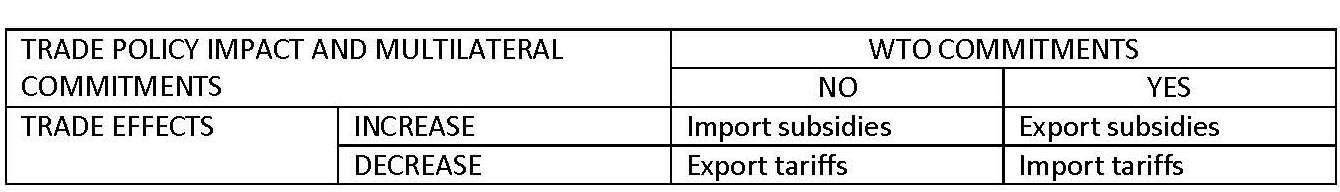

If price transmission exists between global and domestic markets, trade policies can either increase trade flows through subsidies or hamper them through tariff and nontariff barriers. Border controls are relatively easier to enforce, making them more politically feasible; since subsidies require increased budget resources, they can be more politically divisive. Subsidies and tariffs can each be applied to both imports and exports, and the WTO deals with them all differently (see Table 1).

Table 1

Import tariffs have long been the main focus of the GATT negotiations, and the Uruguay Round agreement introduced binding commitments in the case of import tariffs on agricultural products. Export subsidies for industrial products have been prohibited all along. For agricultural products, 25 WTO members are currently allowed to subsidize exports, but they must also commit to eventually reduce those subsidies. On the other hand, import subsidies and export tariffs are not presently constrained; however, Bouet and Laborde rightly point out that the latter are likely to become a new and major bone of contention between high-income countries and agrifood-exporting middle-income countries.

The bias in the WTO’s present commitment structure is clear - import subsidies and export tariffs may be able to insulate domestic markets against international price surges, but they cannot prevent price troughs. Moreover, since WTO commitments are asymmetric, providing ceilings rather than floors, reductions in export subsidies and import tariffs could also be used to compensate for global price increases. According to the present multilateral rules, then, small countries could use trade policies to stabilize their domestic markets only in the case of price spikes. It may make sense to broaden the conditions of the use of the Special Safeguard Clause (at least for poor countries and staple food products) in order to allow national stabilization policies to be more effective in preventing price collapses (Valdes and Foster, 2013).

When small countries may benefit from price stabilization policies, though, we must remain aware that individual countries’ trade policies can sometimes have disastrous effects for others. The present WTO rules may help prevent price drops from being exacerbated by trade policies; however, the currently allowed export restrictions and import subsidies can also induce a vicious cycle in which the adoption of national stabilization policies leads to increased international prices, thus further reinforcing countries’ drive to adopt stabilization policies. Without international commitments, national stabilization policies can easily lead to retaliation by negatively affected trade partners. As a consequence, trade policies can partially cancel each other out in terms of their final impact on prices. This may be good news from the allocative point of view; however, countries differ in size and power and at the end of the day, those on the short side of the market have the upper hand.

This could be seen during the 2006–2008 food crisis, when trade restrictions were imposed by several countries with large populations of poor consumers. It can be argued that the gains seen by poor exporters due to such restrictions outweighed the benefits seen by poor importers. For instance, several Asian countries, including China, India, and Indonesia, isolated their rice industry from the turmoil on the global markets through trade and domestic policies, thus protecting their 3 billion domestic rice consumers; however, this resulted in an increase in market instability for 500 million rice consumers in the rest of the world, particularly in Africa (Timmer, 2009).

Even if, in some cases, the net effect of individual countries’ policies is positive, there is no invisible hand ensuring that this will always be the case. Thus, the world’s least powerful countries would certainly be better off if national trade policies were better coordinated on a multilateral level.

References

Galtier F. 2013. “Managing food price instability: Critical assessment of the dominant doctrine.” Global Food Security 2(2): 72-81.

Timmer C. P. 2009. Management of rice reserve stocks in Asia: Analytical issues and country experience. FAO Expert Meeting on “Institutions and Policies to Manage Global Market Risks and Price Spikes in Basic Food Commodities”, Rome, October 2009.

Valdes, A, and W. Foster. 2003. “Special safeguards for developing country agriculture: a proposal for WTO negotiations.” World Trade Review 2 (1): 5-31.

World Bank. 2005. Managing Food Price Risks and Instability in an Environment of Market Liberalization. Washington DC: World Bank.

Files: