By Antoine Bouet and David Laborde

The nature of the world trading system is deeply mercantilist. Governmental policies are usually aimed at increasing exports and/or decreasing imports, frequently through the implementation of import taxes and export subsidies. Export taxes and export restrictions are a particularly common practice. Numerous developing countries implemented export taxes and export restrictions during the 2006-2008 food crisis: Bangladesh, Brazil, Cambodia, China, Egypt, India, Madagascar, Nepal, Thailand, and Vietnam for rice, and Argentina, India, Kazakhstan, Nepal, and Pakistan for wheat. Looking beyond periods of crisis, export restrictions have also been permanently adopted by countries throughout the world. In 2004, Piermartini noted that approximately one-third of all World Trade Organization (WTO) members impose export duties.

Economic analysis provides several rational justifications for using these export policies:

- Terms-of-trade justification. This is perhaps the most important justification. By restricting its exports, a country that supplies a significant share of the global market in a particular commodity can raise the global price of that commodity. This implies an improvement in that country’s terms of trade. However, it is worth noting that, in the long run, the consequences of such a policy could differ from those originally intended because, as noticed by Mitra and Josling (2009), “producers in the rest of the world will increase their supply in response to higher prices. As a result of increased supply, the price adjusts downward from the short-run level, but still remains above the pre-restriction level.” Therefore, it is quite possible that export restrictions could be beneficial in the short run but have negative consequences in the long run thanks to adjustments in the terms of trade.

- Food security and final consumption price. By creating a wedge between global prices and domestic prices, a government can lower the latter by reorienting the domestic supply toward the domestic market. In 1994, the Indonesian government imposed export taxes on palm oil products, including crude and palm cooking oil, because it considered cooking oil to be an “essential” commodity (Piermartini, 2004). This rationale was often used again during the food crisis of 2006–2008 to justify the implementation of export taxes and other forms of export restrictions.

- Intermediate consumption price. Export taxes on primary commodities (especially unprocessed ones) work as an indirect subsidy to higher-value-added manufacturing or processing industries by lowering the domestic price of inputs compared to their global—non-distorted—price. While the previous justification addresses the use of export taxes to lower the price for final consumption, this justification is concerned with decreasing prices for intermediate consumption. For example, in 1988, Pakistan imposed an export tax on raw cotton in order to stimulate the development of the cotton yarn industry. Similarly, export taxes on palm oil are imposed in Indonesia and Malaysia in order to support the development of downstream industries (in these cases, biodiesel and cooking oil). This kind of “degressive export tax structure” (taxes are greater than zero for the raw commodity and zero or close to zero for the processed good) results in an expansion of the production volume of the manufacturing sector, to the detriment of the raw commodity.

- Public receipts. Export taxes provide revenues for developing countries that have limited capacity to rely on domestic taxation.

- Income redistribution. Like import tariffs, export taxes imply redistribution of income to the detriment of the domestic producers of the taxed commodity and to the benefit of domestic (final or intermediate) consumers and public revenues.

Countries have a relatively large degree of freedom in the implementation of such taxes, as the WTO does not prohibit export taxes and other forms of export restrictions. More precisely, as stated by Crosby (2008), “General WTO rules do not discipline Members’ application of export taxes,” but “they can agree—and several recently acceded countries, including China, have agreed—to legally binding commitments in this regard.” In addition, the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture stipulates that when implementing a new export restriction, a WTO member must (i) consider the implications of these policies for the food security of importing countries, (ii) give notice to the Committee on Agriculture, and (iii) consult with WTO members that have an interest in the commodity to be taxed. However, this agreement does not institute any penalty for countries that ignore the rules.

So economic theory provides some justification for the implementation of export taxes. However these taxes are non-cooperative policies that lead to higher world food prices; this dynamic is amplified in times of food crisis and already-increasing global food prices. Of course, export taxes are not the only trade policies that may contribute to higher world food prices. In times of crisis, food-importing countries may react by decreasing their import duties, increasing demand on the world market and thereby raising global prices yet again. This is in particular true for large countries.

We used the MIRAGE model of the world economy to assess the economic consequences of various trade policy scenarios related to the imposition of additional export taxes and the decrease of import duties in a period of food crisis. Our scenarios evaluate the impact of trade policies (implemented through either variation of import duties or variation of export taxes) on world prices and national real incomes. We supposed that these trade policies are aimed at keeping the domestic price of an agricultural commodity constant, despite a shock to the global price of that commodity. In other words, these are clearly food security policies. Our objective is to understand the international implications of such ‘beggar-thy-neighbor’ policies on world prices and national real income, in particular for small countries.

The first scenario is called “Base” and represents a demand shock in the wheat sector in which the global price of wheat is augmented by about 10 percent. We then endogenize export taxes in net wheat-exporting countries so that the real domestic price of wheat remains constant (scenario ET). The next scenario is an endogenization of import taxes (scenario IT) under the same objective in net wheat-importing countries. As scenario IT implies the adoption of import subsidies, we implement another scenario in which the decision to decrease import taxes is limited by 0 (free trade); this scenario is called IT0. Finally, we study two scenarios that cumulate two political situations described earlier: i) import taxes are fixed at the level of scenario IT and export taxes are endogenous so that the real domestic price of wheat remains constant (called scenario ETIT) and ii) import taxes are fixed at the level of scenario IT0—no import subsidy—and export taxes are endogenous so that the real domestic price of wheat remains constant (called scenario ETIT0).

If we consider the import taxes required by net wheat-importers to keep the domestic price of wheat constant, we see that variations in import tariffs are substantial, in particular in the Middle East and North Africa (-41.9%) and the “rest of Europe” region (-32%). For instance, Egypt and Thailand would be obliged to implement an import subsidy in order to keep the domestic price of wheat constant.

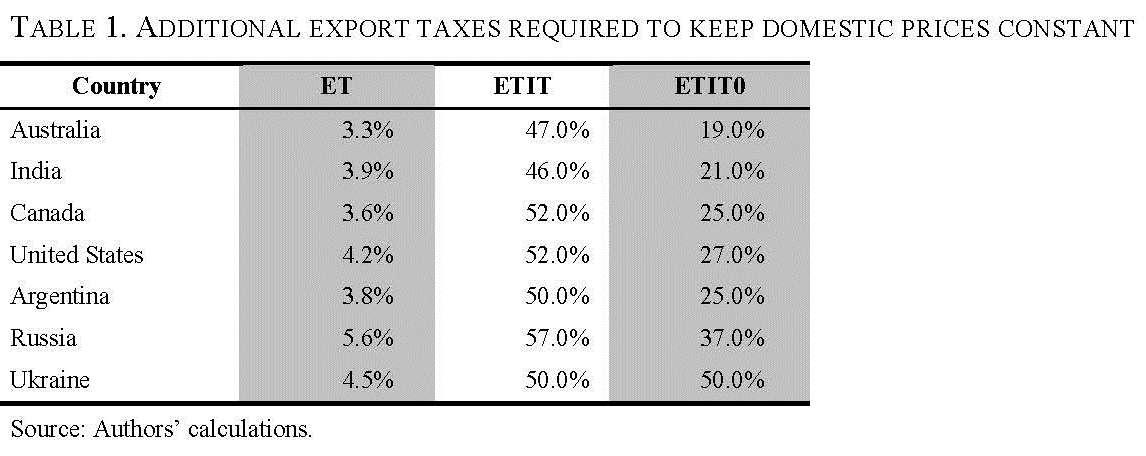

Table 1 presents the augmentations of export taxes needed to keep the domestic price of wheat constant in net wheat-exporting countries under three scenarios. When only export taxes are implemented by net wheat exporters, the changes in export taxes are systematically less than 6 percent; they are always more than 45 percent when import taxes are also implemented by net wheat importers. This illustrates the interdependence of trade policies and shows how a process of retaliation and counter-retaliation can worsen the whole process of political decision-making. If no import subsidies are implemented (column ETIT0), which may be a more realistic scenario, the changes in export taxes are much less important but remain substantial, in particular as compared to scenario ET. In this case, export taxes range from 19 percent to 50 percent.

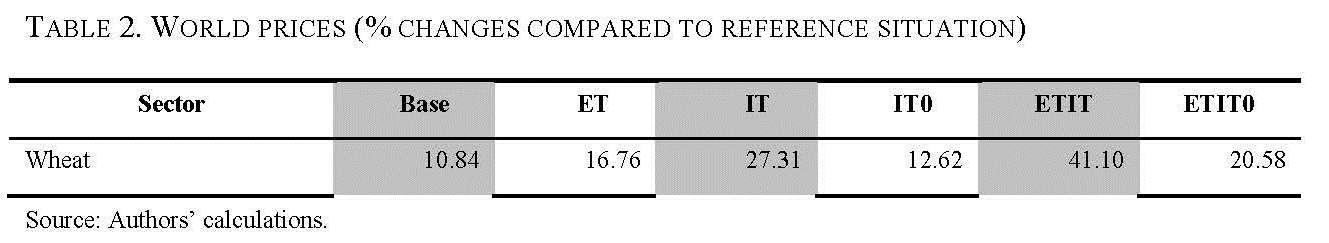

Table 2 indicates how global prices for traded quantities of agricultural goods are affected in the various scenarios. Almost all agricultural prices are positively affected by various shocks due to substitution effects on the demand and supply sides, but wheat is by far the most exposed to global price shocks. Table 2 focuses on this commodity. While the global wheat price increases by 10.8 percent thanks to a demand shock, it increases by 16.8 percent when net wheat exporters react by increasing export taxes. Therefore, this policy reaction is a ‘beggar-thy-neighbor decision.’ In other words, it is a rational decision from the single-country point of view, but it amplifies negative aspects of the initial shock for other countries. The effects are even larger when net wheat-importing countries implement reductions in import tariffs (27.3 percent). When no import subsidies are implemented, the impact of import taxes on global prices (12.6 percent) is much more comparable to the impact of export taxes. Finally, the combination of increased export taxes by net wheat exporters and reduced import taxes by net wheat importers causes a dramatic increase in this commodity’s global price (41.1 percent when import subsidies are implemented; 20.6 percent when they are not), as the disconnection between domestic and global prices is fueled by border distortions.

In sum, export taxes are typically “beggar-thy-neighbor” policies that deteriorate the terms of trade and real incomes of countries’ trading partners. This often leads to retaliation by partners whose terms of trade have been negatively affected by initial export taxes. The 2006–2008 food crisis clearly illustrates this point about retaliation and counter-retaliation in response to reduced import duties and augmented export taxes.

It should be noted that the impacts of export policies can differ depending on a country’s size. Large countries can implement beggar-thy-neighbor policies that increase their own national welfare at the expense of the welfare of their trading partners, small countries do not have this option. Changes in small countries’ own policies neither improve their own welfare nor harm their partners’ situations.

Because of their potentially harmful impacts, and their varying power for large and small countries, the issue of export taxes and restrictions remains a touchy one. Today, the European Union and the United States are wondering whether certain Chinese export taxes (on rare earths in particular) are consistent with WTO standards, and whether they can bring their case to the WTO dispute settlement body. In 2008, China raised export taxes on some metal products, such as parts of steel products, metal ore sand, and ferro-alloys. The objective of this policy was to reorient these goods to the domestic market in order to decrease the price of intermediate goods for domestic manufacturing sectors. It is understandable that the European Union has proposed to discipline such practices. While this proposal has been well received by countries such as Canada, the United States, Switzerland, and Korea, it has been highly criticized by some developing countries such as Argentina, Malaysia, Indonesia, Brazil, Pakistan, Cuba, India, and Venezuela, with Argentina leading the opposition. The reasons advanced by this latter group of countries is that “export taxes are a right and a legitimate tool for developing countries; they help increase fiscal revenue and stabilize prices; there is no legal basis for a negotiation; there is no explicit mandate for a change in WTO rules on this issue” (Raja, 2006). It is worth noting that the European Union makes a distinction between trade-distorting taxes and “legitimate” export taxes such as those applied in the context of balance-of-payments imbalances. The European Union proposes a full prohibition of trade-distorting export taxes, and the EU and the United States frequently implement bans of export taxes in bilateral agreements that they negotiate.

The European Union has been very active in demanding substantive commitments by all WTO members to eliminate or reduce export taxes under the Doha Development Agenda. Bringing some penalties into the WTO context in the area of export taxes may be justified, as such penalties exist in the domain of import tariffs. Moreover, net food-importing small countries that can be significantly harmed in the event of a food crisis and by the escalation of export taxes throughout the world should continue to be considered, since they do not have many policy instruments with which to address this kind of issue on their own. Export taxes and export restrictions could clearly become a new and major bone of contention between high-income countries and agrifood-exporting middle-income countries in trade negotiations.

References

Piermartini, R. 2004. The role of export taxes in the field of primary commodities. WTO Discussion Paper. Geneva: World Trade Organization.

Mitra, S., and T. Josling. 2009. Agricultural export restrictions: Welfare implications and trade disciplines. IPC Position Paper, Agricultural and Rural Development Series. Washington, D.C.: International Food and Agricultural Trade Policy Council.

Crosby, D. 2008. "WTO legal status and evolving practice of export taxes." Bridges 12(5).

Raja, K. 2006. "Clash in NAMA talks on proposed export-tax rules." SUNS , June 1.

Files: