When it comes to resilience, we must put vulnerable farmers in the driver's seat

By Indira Joshi

From the 2015-2016 El Niño to the exceptionally strong 2017 hurricane season in the Caribbean to the devastation wrought in southern Africa in 2019 by Cyclone Idai, small-scale agricultural communities across the globe are bearing an increasing burden of disaster impacts. With global food security dependent on a productive and resilient agriculture sector, protecting agriculture from the impacts of natural disasters is of paramount importance – especially as the planet’s population continues to grow, demands on productive resources increase, and climate-related shocks become more frequent and more intense.

To be truly effective, durable, and scaleable, however, solutions that seek to build resilience must position vulnerable communities and households not just as active participants process but as the engine that drives the process.

Since 2008, FAO and its partners worldwide have implemented a rural community-driven approach called Caisse de Resilience ("resilience toolbox" or CdR) that aims to empower and increase the resilience of vulnerable households by strengthening their technical, social, and financial capacities to better manage risks and seize local opportunities. Because women and youth are key actors in agricultural livelihoods and other economic opportunities, the CdR approach tends to work mainly through women’s associations, youth groups, and farmer groups of which the majority are women smallholder farmers.

The approach was pioneered in the disaster-prone region of Karamoja, Uganda to help vulnerable agro-pastoralist households engage in more resilient livelihoods and reduce their risk of and vulnerability to recurrent shocks and crises. The striking feature of this effort is the fact that it places vulnerable communities at the center of risk management.

Tailored to context

Within the framework of FAO’s resilience building programme and under the Organization's Regional Initiative “Building resilience in the drylands of Africa”, the CdR approach has been initiated in numerous countries in the Horn of Africa, Sahel, West Africa, and Central America. The approach can be tailored to various contexts; it been used to address needs ranging from emergency and rehabilitation situations to development challenges and has proved to be an excellent means with which to bridge humanitarian and development assistance. More broadly, CDR has been used to provide support in marginal and fragile ecosystems prone to hydrological hazards, extreme weather conditions and climate-related shocks, environmental degradation, weak productivity and deteriorating rangelands, as well as for the recovery of former refugees and displaced people and the stabilization of conflict-affected communities.

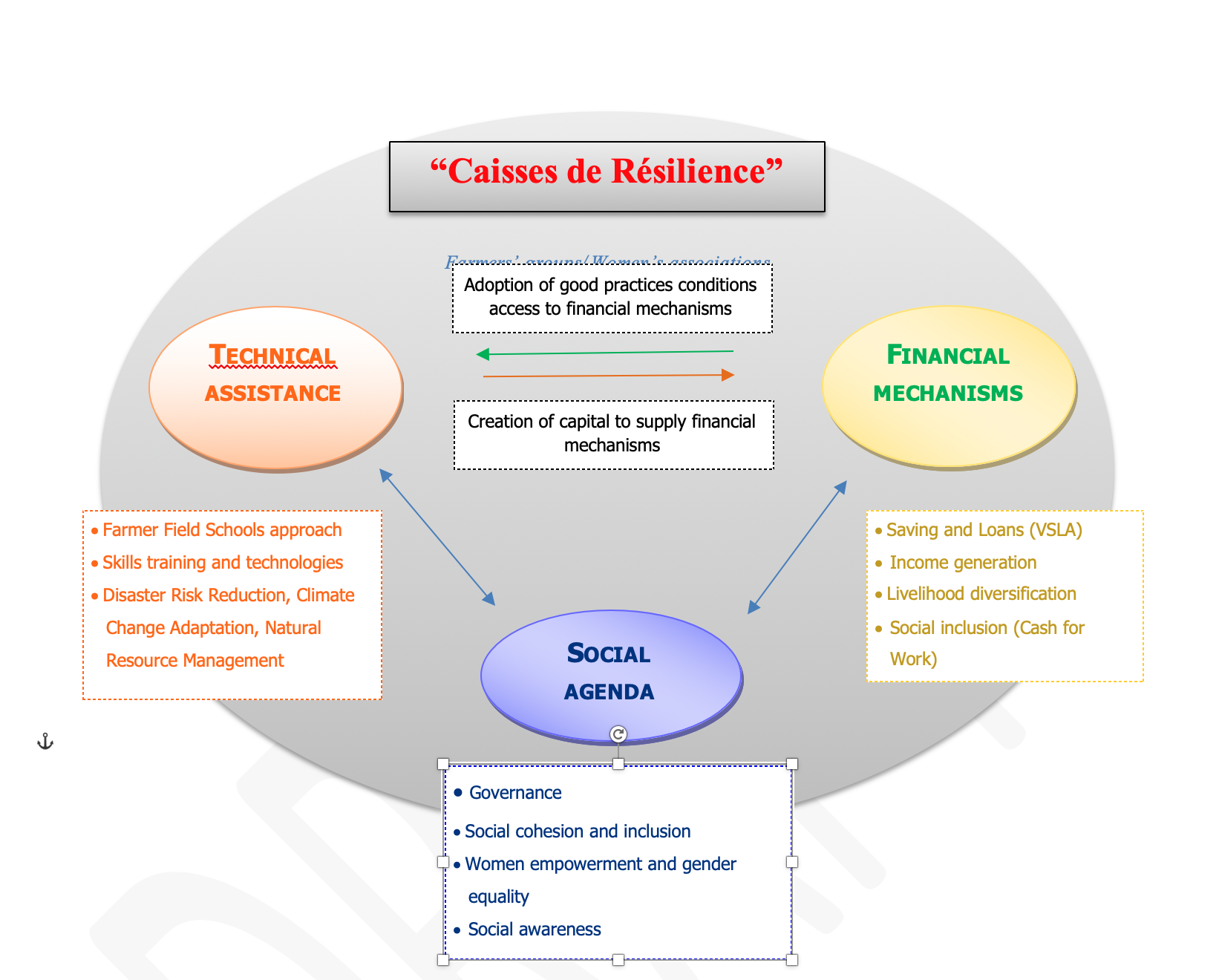

Three mutually reinforcing dimensions

The three key pillars of the CdR approach – technical, financial, and social assistance - depend on context and are determined through an initial diagnosis and risk identification process at the community level. This participatory risk analysis forms the basis for a shared action plan to guide community-led activities. In some contexts, such as the Sahel, the focus is on climate-related risks and high levels of malnutrition. In the Dry Corridor in Central America, the focus has been on applying disaster risk reduction good practices at the farm level and increasing communities’ disaster preparedness. In the Central African Republic, projects mainly focus on raising people's agricultural productivity, improving post-harvest food management, and enhancing farmers' access to markets. Other projects, such as in Liberia, have addressed social cohesion challenges and livelihood disruption. Although the specific activities depend on local challenges and priorities, the key aspect of CdR is that the three dimensions work together to offer an integrated package of support.

These three dimensions provide mutually reinforcing benefits for people’s lives and livelihoods through the accumulation and diversification of assets and income sources, two key dimensions for increasing resilience.

- The technical pillar reinforces farmers’ capacities and community engagement to work on catchment-based interventions and to implement good agricultural and environment practices and technologies. The good practices promote sustainable production, reduce vulnerability to shocks, and contribute to improving natural resource management. The new acquired skills can provide farmers an opportunity to diversify and engage in more sustainable livelihood options.

- The financial pillar focuses on developing a culture of saving and responsible, sustainable investment through rural microfinance mechanisms, such as Village Saving and Loan Associations (VSLA), which can be complemented by an emergency/solidarity fund triggered in case of shocks. The financial pillar enables farmers to make small investments to improve production and/or complement other income-generating activities for more regular and stable incomes. The aim is to help vulnerable households move out of the vicious circle of poverty and vulnerability by building capital and encouraging market access, small-scale businesses, and investment opportunities for growth.

- Social activities strengthen community-based groups that can be a platform for social inclusion, solidarity, common planning for action, problem solving, and knowledge exchange. Group members then serve as an entry point into the community to address social challenges

such as nutrition, literacy, gender-based violence awareness, conflict resolution, health care, etc.

Key features of the CdR approach

- Conditionality: Some groups have conditioned access to saving and loans schemes for the implementation of good agricultural, environmental, or social practices. Members engage for short-term benefits (access to credits and technologies), but the groups themselves can also work for longer-term impacts (climate change adaptation, land and water conservation, biodiversity, ecosystem recovery, improved nutrition, gender equality, girls’ schooling, etc.).

- Group cohesion: Social strengthening builds trust between group members and encourages the responsible use of group capital, which is essential for a sustainable credit system. Intra- and inter-group interaction fosters cohesion and exchange of good practices and triggers advantages for the entire community.

- Women’s empowerment: Providing women with access to new skills, financial resources, and an informal social safety net contributes positively to gender equality.

- Safety net and social protection: Access to credit and savings at the community level enables people to break the cycle of vulnerability and become more resilient to shocks.

Transformational change

The CdR approach is an effective way to help groups shift from subsistence agriculture to market-oriented livelihoods because it provides members with the means to take up new opportunities throughout the whole production chain. It also forms a good basis for initiating transformative actions, such as larger-scale community-based watershed management activities.

To enable the program’s replication and upscaling, it is crucial to develop and sustain partnerships with governments, UN agencies, and civil society organizations. CdR can easily be integrated into regional initiatives that support resilience, such as the Global Alliance for Resilience Initiative (AGIR), the Great Green Wall in the Sahel and West Africa, the Intergovernmental Authority in Development (IGAD)’s Drought Disaster Resilience and Sustainability Initiative (IDDRSI), the Horn of Africa Resilience (SHARE), or the Renewed Efforts Against Child Hunger and Undernutrition (REACH) in different countries.

By supporting smallholders through capacity development and contributing to resilient ecosystems, the CdR approach can drive sustainable development, which has long-lasting impacts that continue long after the core projects wind down.

Indira Joshi is a Liaison and Operations Officer with the Emergency and Resilience Division of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations.

This piece is a guest blog and does not necessarily represent the opinions of IFPRI, the Food Security Portal, or its donors.

Files: