Related blog posts

This post originally appeared on IFPRI.org blog.

In a recent blog post, we analyzed how the spread of the disease associated with the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) may bring damage to the global economy, and with it to food security and efforts to reduce poverty. We emphasized that the economic impacts of the present pandemic will be different from previous ones, including SARS, avian influenza, and MERS, which caused direct damage to livestock sectors, leading to food shortages and food price hikes in affected areas. No major food shortages have emerged thus far because of COVID-19.

However, the pandemic is having significant economic impacts. It is rattling global stock markets and economic activity has slowed dramatically in places where many people are ill and movements are restricted to contain further spread of the virus. Signs of continuing economic slowdown are most visible in China, but due to broader containment measures elsewhere, including restrictions on travel, shutdowns of bars, restaurants, and other gathering places, and additional limits placed on services, the economic impacts are now spilling across countries. Fears for a global economic slowdown are increasing. Economic forecasters project global growth could be cut in half in 2020, to 1.5% from an earlier forecast of 3%. In our previous post, we projected that for any one percentage point slowdown of the global economy, the number of poor—and with it the number of food insecure people—would increase by 2%, that is, by 14 million people (and possibly more depending on the nature of the economic disruptions). Here we explain how we reached this estimate. These impacts are as yet hard to predict, since so much is unknown about COVID-19, including how fast it may spread and how effective containment measures will be. The demographic profile of people affected by COVID-19 suggests the direct economic effects of coronavirus-related morbidity and mortality may be more muted than in pandemics like the Spanish flu of 1918, whose impacts fell most heavily on young people, including many in rural communities. Thus far, older people with poor health have been shown to be by far the most vulnerable to becoming seriously ill with COVID-19. Most people in this group are not in the work force. Aside from increased healthcare costs and lost productivity, the economic damage is thus likely to be felt mainly through the impacts of the restrictions on people going to work, on travel, and on social interaction. In the present scenario analysis, we assume containment measures will prove effective in slowing the spread of the virus over the coming months, so that its main economic impact is a major, but short-lived disruption of global economic activity. A rebound would likely follow, once movements of people, goods and services begin to return to normal. This scenario resembles that underlying OECD’s projected global economic growth slowdown of between 0.5 and 1.5 percentage points in 2020. The implications of such a slowdown for poverty and food insecurity depend on the assumptions made about the duration of the pandemic and transmission mechanisms. On the duration, as mentioned we assume, perhaps optimistically, that the global spread of the virus may be contained within the next few months, so the global economy need not fall into a deep recession, but slow by one percentage point during 2020. We represent the economic impacts through three possible scenarios:

- Labor productivity shock: Major impacts come from workers unable to do their jobs. resulting in an average decline in labor productivity of 1.4% during 2020. (This would be equivalent to a 1.4% drop in labor supply).

- Total factor productivity shock: Impacts are felt through a temporary paralysis of domestic economic activity caused by disruptions to distribution channels, inability to provide inputs and services due to quarantines for workers, and so on. We simulate this through an average reduction in total factor productivity growth big enough to reduce global GDP by 1%.

- Trade shock: Impacts are felt through international trade disruptions leading the cost of doing trade to increase by almost 5% on average and enough to provoke a global economic growth cost of 1%.

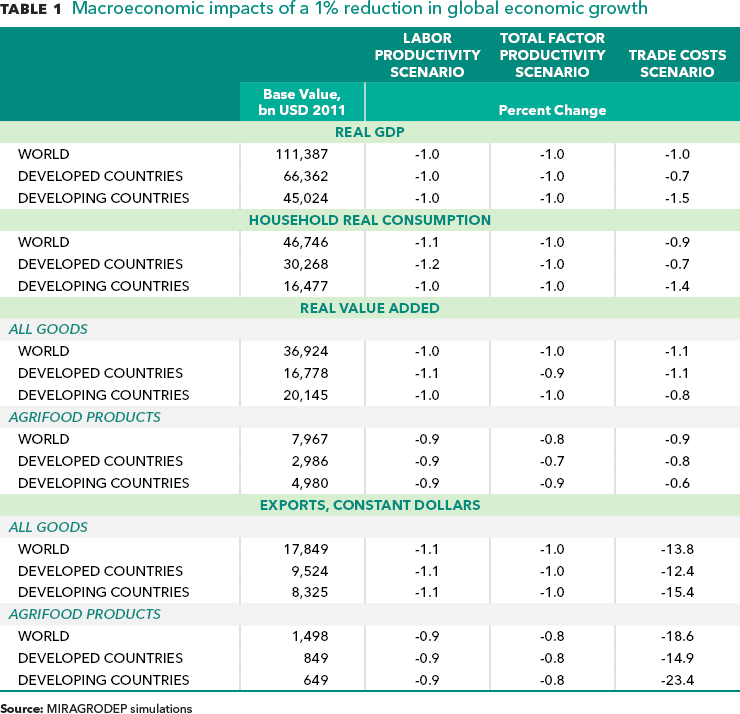

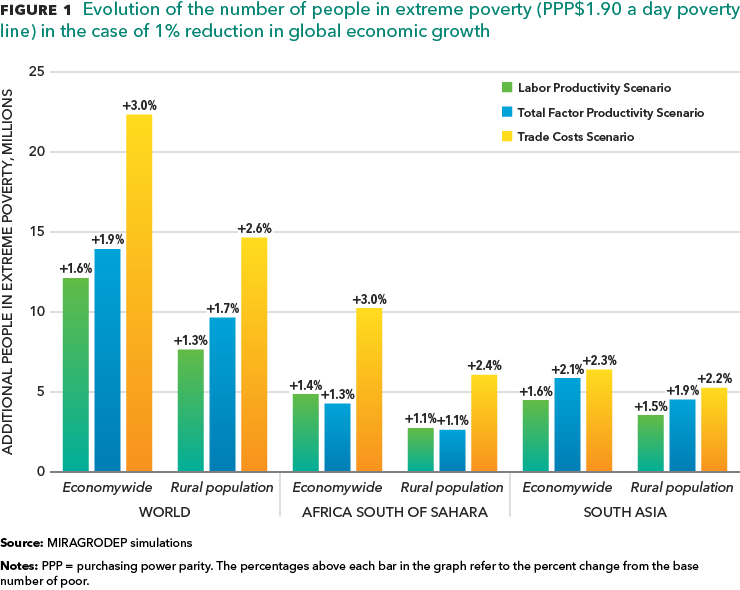

We run these scenarios with IFPRI’s global general equilibrium model, MIRAGRODEP, to generate impacts on income, wages, and key commodity prices across countries, and calculate the poverty impacts at the household level, using household models for about 300,000 households across the developing world. In doing so we follow the same approach as for previous assessments we have made of the poverty impacts of global economic slowdowns. These assessments take into account the direct impacts of productivity declines on the income generated in household businesses, and the impacts of all productivity declines on producer and consumer prices (particularly food prices), as well as on wages. The main findings are in the table and graph below, showing the simulated changes relative to baseline values, with millions of additional poor people resulting under each of the three scenarios. Overall, the results show that the macroeconomic impacts on GDP, household consumption, agri-food production and trade would be broadly similar for developed and developing countries—if the slowdown were caused by the labor productivity or total factor productivity shocks. However, if the impacts of containment measures are instead felt primarily through disruptions in international trade, there would be more severe consequences for developing countries because of their greater dependence on trade. As shown in Table 1, developing country GDP growth would decelerate by 1.5% in the trade shock scenario, while that of developed countries would drop by 0.7%. The agri-food sector appears to be more resilient than others in all scenarios, in part because food demand is relatively less sensitive to income growth (that is, income “inelastic” in economists’ jargon). However, the global food system itself would suffer a greater adverse impact in the trade shock scenario, in which case a 1% global economic slowdown could cause a decline in developing-country agri-food exports of almost 25%.  Overall, 1% lower growth in the world economy would translate into an increase in the global extreme poverty rate of between 1.6% and 3% (see Figure 1)—the range due to the fact that poverty impacts are quite sensitive to whether the slowdown is through productivity or trade disruption shock differences. For the temporary, partial paralysis of business activity caused by COVID-19 containment measures, global poverty would increase by a simulated 14 million people (a 1.9% increase in the total factor productivity scenario). But this number would increase to 22 million (3.0% increase) if trade channels were disrupted.

Overall, 1% lower growth in the world economy would translate into an increase in the global extreme poverty rate of between 1.6% and 3% (see Figure 1)—the range due to the fact that poverty impacts are quite sensitive to whether the slowdown is through productivity or trade disruption shock differences. For the temporary, partial paralysis of business activity caused by COVID-19 containment measures, global poverty would increase by a simulated 14 million people (a 1.9% increase in the total factor productivity scenario). But this number would increase to 22 million (3.0% increase) if trade channels were disrupted.  The simulation results for the poverty impacts by region show some sensitivity to the nature of the transmission channel. In absolute terms, the greatest regional poverty impact would fall on Africa south of the Sahara, where 40-50% of the global poverty increase would be concentrated. In relative terms, the impact of a trade shock would affect Africa’s poor more than South Asia’s, given that Africa’s economies are—on average—more dependent on trade than those South Asia, given the weight of India, a large but relatively closed economy. The productivity shocks, in contrast, would have a bigger impact on poverty in South Asia than in Africa, possibly because the bigger adverse impact in the scenarios on non-agricultural sectors, which have a larger weight in South Asian economies. More detailed results of these simulations can be found here. Rob Vos is the Director of IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions Division (MTID); Will Martin and David Laborde are MTID Senior Research Fellows.

The simulation results for the poverty impacts by region show some sensitivity to the nature of the transmission channel. In absolute terms, the greatest regional poverty impact would fall on Africa south of the Sahara, where 40-50% of the global poverty increase would be concentrated. In relative terms, the impact of a trade shock would affect Africa’s poor more than South Asia’s, given that Africa’s economies are—on average—more dependent on trade than those South Asia, given the weight of India, a large but relatively closed economy. The productivity shocks, in contrast, would have a bigger impact on poverty in South Asia than in Africa, possibly because the bigger adverse impact in the scenarios on non-agricultural sectors, which have a larger weight in South Asian economies. More detailed results of these simulations can be found here. Rob Vos is the Director of IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions Division (MTID); Will Martin and David Laborde are MTID Senior Research Fellows.